When it comes to searching for genealogical information, researchers with German ancestry have the advantage of access to many high-quality published secondary sources. Prime among these are Ortssippenbücher (OSBs), which I described in the June 2019 issue of the SK Translations newsletter. Hofgeschichten and Häuschergeschichten are additional sources that can provide valuable information about your ancestor.

Hofgeschichten are farm histories (Hof means farm). Häuschergeschichten are building histories (Haus means house but can refer generally to a building). Both types of publications pertain to a specific village or town and include chronologies of each property in the community listing a succession of occupants. Häusergeschichten, as the name suggests, usually include a construction history of the property, although Hofgeschichten can also include this type of information.

For the most part, the succession lists (Höfefolgen or Bestizerfolgen) pertain to tenants, as property ownership was usually impossible for common people until the late 18th to mid-19th centuries. Leases were heritable depending on the area of Germany, making it feasible for a family to occupy a property over many generations. This feature can make the lists useful for connecting generations.

Data is commonly extracted from tithe and tax records and may be supplemented by genealogical information from church records. Non-German speakers should be able to decipher the information in the lists if they can identify common words and abbreviations.

The chronological lists usually appear in the context of a broader local history that can help researchers ground their ancestral research in the larger historical and social context. Information can include historical development of the community, descriptions of churches and other important institutions, lists of war casualties, information about emigrants from the village, and maps and photographs. Researchers who do not read German may want to consult a translator in order to glean this information.

Example: Oberpreuschwitz

A farm history for the village of Oberpreuschwitz near Bayreuth, Bavaria was written by Ernst Wiedemann and published in Archiv für Geschichte von Oberfranken, Band 47 (1967) (Bayreuth: Historischer Verein für Oberfranken), pp. 7–110 under the title, “Hofgeschichte der Gemeinde Oberpreuschwitz, Kreis Bayreuth”.

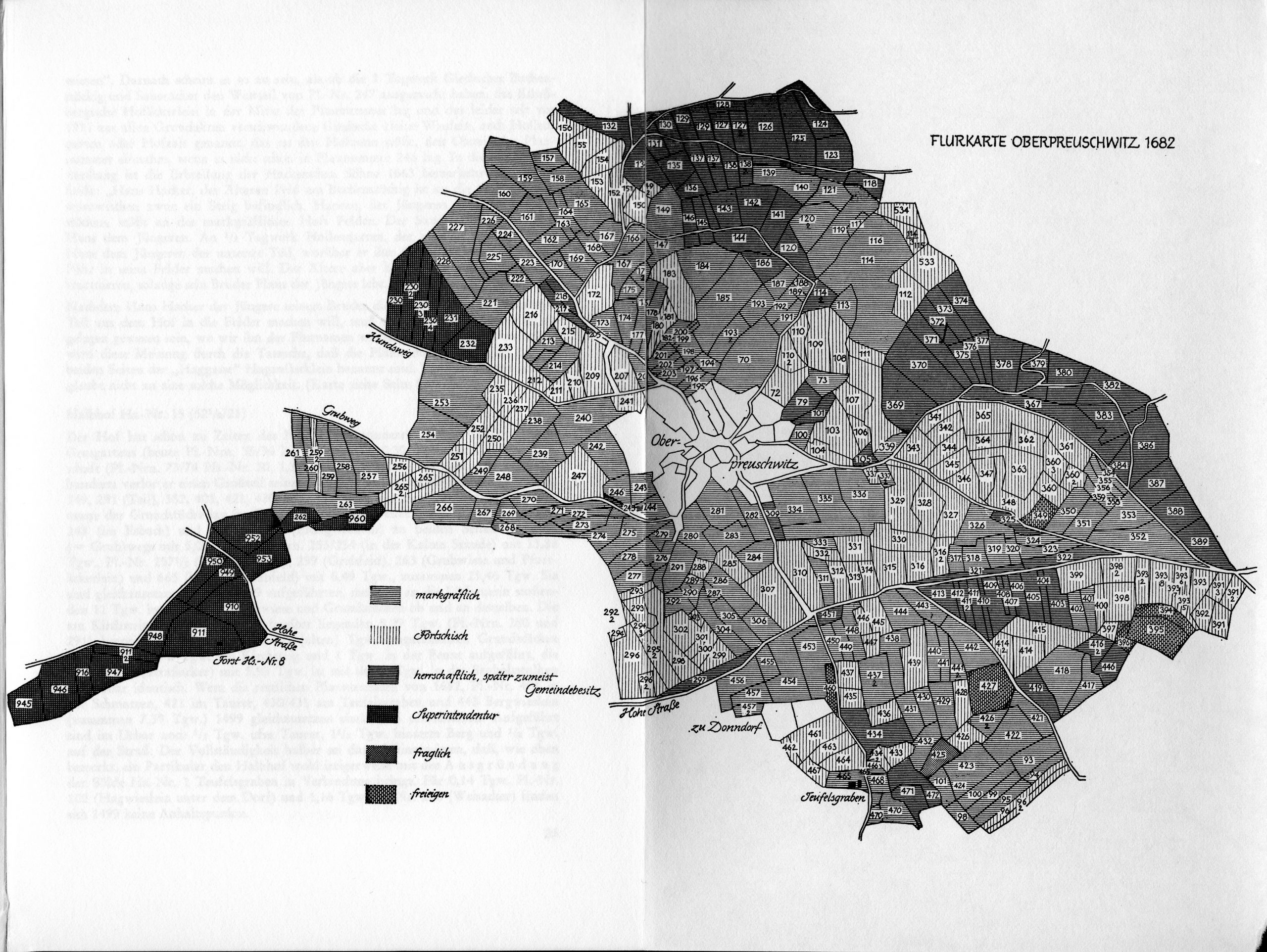

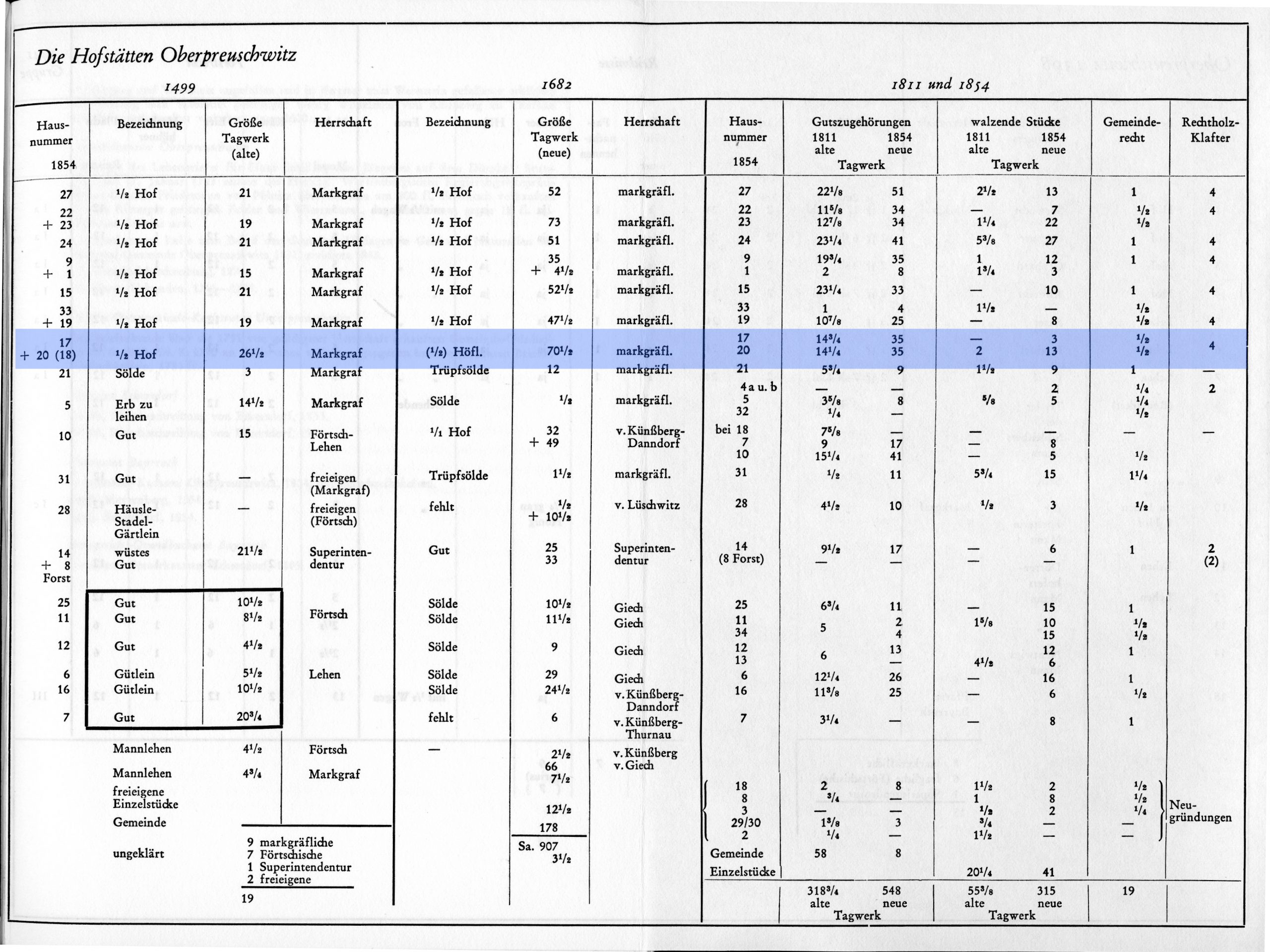

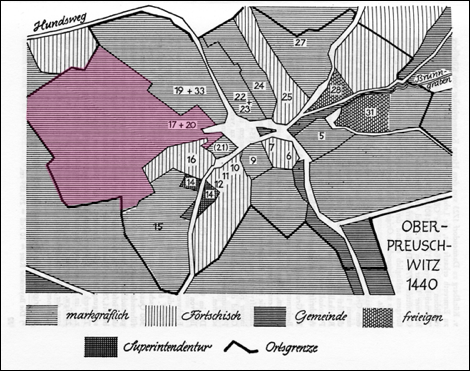

The Hofgeschichte for Oberpreuschwitz begins with narrative sections outlining the historic development of the community through its land divisions among various landholders, and descriptions of the boundaries, characteristics, and ownership of the fields related to each house number.

The main section features the Besitzerfolge, a farm-by-farm chronological listing of successive occupants. The article also includes a Hofgeschichte of the neighboring hamlet of Unterpreuschwitz. The chronologies are followed by lists of sources used, a table summarizing tax-list data, and a name index.

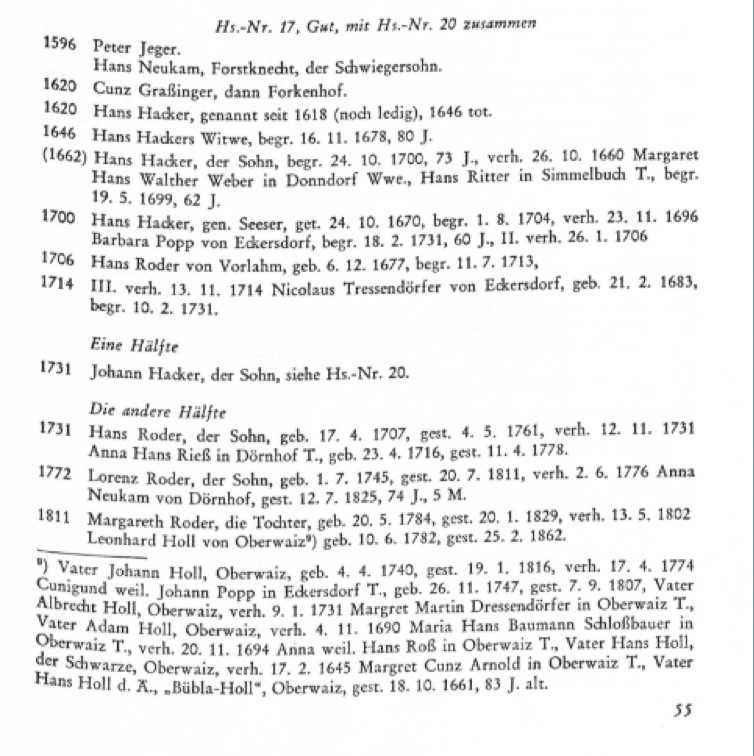

The following chronology appears on pp. 55–56.

TRANSLATION:

House No. 17, a manor, together with House No. 20.

1596 Peter Jeger and his son-in-law, Hans Neukam, a forest worker.

1620 Cunz Graßinger, subsequently Forkenhof

1620 Hans Hacker, mentioned since 1618 (still unmarried), died 1646.

1646 Hans Hacker’s widow, buried 16 Nov. 1678, 80 years old.

(1662) Hans Hacker, the son, buried 24 Oct. 1700, 73 years old; married on 26 Oct. 1660 to Margaret, widow of Hans Walther in Donndorf and daughter of Hans Ritter in Simmelbuch, buried on 19 May, 1699, 62 years old.

1700 Hans Hacker, birth name Seeser, baptized on 24 Oct 1670, buried on 1 Aug. 1704, married on 23 Nov. 1696 to Barbara Popp from Eckersdorf, buried on 18 Feb 1731, 60 years old. Second marriage on 26 Jan. 1706 to:

1706 Hans Roder from Vorlahm, born 6 Dec. 1677, buried 11 July 1713.

1714 Third marriage (of Barbara Popp) on 13 Nov. 1714 to Nicolaus Tressendörfer from Eckersdorf, born 21 Feb. 1683, buried 10. Feb. 1731.

First half

1731 Johann Hacker, the son [of Hans Hacker and Barbara Popp], see House Nr. 20

The other half

1731 Hans Roder, the son [of Hans Roder and Barbara Popp], born on 17 April 1707, died on 4 May 1761, married on 12 Nov. 1731 to Anna, daughter of Hans Rieß in Dörnhof, born on 23 April 1716, died on 11 April 1778.

1772 Lorenz Roder, the son, born 1 July 1745, died 20 July 1811, married on 2 June 1776 to Anna Neukam from Dörnhof, died 12 July 1825, 74 years and five months old.

1811 Margareth Roder, the daughter, born on 20 May 1784, died on 20 Jan. 1829, married on 13 May 1802 to Leonhard Holl from Oberwaiz, born on 10 June 1782, died on 25 Feb. 1862.

1844 Johann Holl, the son, born 6 July 1818, died 1 Feb. 1886, married on 13 May 1845 to Anna Barbara, daughter of Adam Hacker, born 19 July 1821, died on 24 June 1893.

1889 Konrad Holl, the son, born 13 July 1864, died 17 June 1921, married 1 July 1890 to Kunigund Margaret, daughter of Konrad Kirschner in Melkendorf, born 10 July 1871, died 9 Feb. 1953.

1928 Adam Holl, the son, married on 5 Jan. 1938 to Margaret Körber from Unterpreuschwitz.

ANALYSIS:

This example shows that the farm at House No. 17 had been occupied by the Hacker family beginning in 1620. In 1700, Hans Hacker became the occupant. When he died in 1704, his widow, Barbara, married two more times, first to Hans Roder in 1706 and, after his death, to Nicolaus Tressendörfer. Both Barbara and her third husband died in 1731. The property was then divided between Johann Hacker, a son from her first marriage, and Hans Roder, a son from her second marriage. The property was split so that both sons could inherit tenancy. Johann Hacker occupied one section of the property, which was designated as House No. 20, and whose chronology continues in a separate list. In 1811, Margaret Roder inherited the property. She married Leonhard Holl in 1802, and the property continued in the possession of the Holl family until the end of at least 1928, when the list ends. A footnote next to Leonard Holl’s name on the bottom of page 55 in this example lists his direct ancestors back to Hans Holl, Sr., who was born about 1588.

FINDING HOF– AND HÄUSERGESCHICHTEN

Some Hof- and Häusergeschichten are stand-alone publications, but many are included in histories of the local community. Look for books in which the village name is the title and words such as Geschichte, Chronik, Hofgeschichte, Hausgeschichte, Höfe, Häuser, and Heimatkunde (local history). The following are examples of titles:

- Häuserchronik Braschstadt

- Häusergeschichte Kirchberg bei Simbach am Inn

- Häuser und Höfe von Paitzdorf und Mennsdorf

- 500 Jahre Haus- und Hofgeschichte von Bobing

- Holzgünz: Heimatkundliche Beiträge zur Geschichte der Ortsteile Ober- und Unterholzgünz

Hof- and Häusergeschichten also appear as articles in journals published by genealogical and historical societies in Germany.

The St. Louis County Library History & Genealogy Department actively collects these and other sources for German research. Search the library’s catalog at https://webpac.slcl.org/ or contact the History & Genealogy Department at genealogy@slcl.org. Other libraries with sizable German research collections may also have them, and they are usually listed in WorldCat. Many are available for sale at abebooks.com and other online book sellers, as well.

Locating Hof- and Häusergeschichten for a village or town and interpreting the information in them can be a challenge, but the results can yield and substantial amount of genealogical data pertaining to your ancestor and valuable historical and cultural information to add to your family’s history.

Scott Holl is manager of History & Genealogy at St. Louis County Library in St. Louis, Missouri. He holds a BA in German from Fort Hays State University, an MA in Theology from the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, and an MLIS from Dominican University in River Forest, Illinois.

11 Responses

Great article! Have you seen the book Bauernhofbilder des Altenburger Landes? It is out of print, but the drawings are remarkable. I wish my German was better to translate the written part. Many old farm buildings still stand in the old East Germany, a mix of disrepair and well preserved. My great great grandparents emigrated from Tegkwitz Germany in 1867.

Thank you for mentioning the book. I will see if I can get a copy for our library.

Scott I’m hitting a dead end with my Great grandfather wilhelm Friedrich Federer born in Urloffen and emigrating to St. louis in 1868…can you help

Oh, I would treasure this information! My grandmother came from a small village in south western Germany, Plaidt. I will try and find the farm history of her family, I know her father owned land and a farm and now it is making me wonder how far back that went.

Our library does not have a Hofgeschichte for Plaidt, but we do have an Ortssippenbuch covering the 18th-20th centuries that has genealogical information about individual families. The title is “Familienbuch Plaidt II” by Karl Heinz Scheuren and Klaus Marzi (Plaidt: Cardamina Verlag, 2012). Our staff can look up the family name in the book and sent you scans of the pages. Submit a request using the online form at https://www.slcl.org/content/lookup-request.

Great article. Thank you.

Thank you for such a great and interesting article. I especially appreciate the suggestions for how to search for farm and building books.

I am interested in the tradition of “farm names” I have an ancestor, Ferdinand Friedrich Wilhelm “William” Bölk genannt Busacker, whose mother was Sophia Bölk. I believe when a man married a woman who inherited farm property that it was customary for the man to adopt the farm name in this context … “farm name” genannt surname (e.g. Bölk genannt Busacker). If my understanding of the tradition is correct, then should a search for the husband’s and wife’s ancestors pursue the farm name, the surname or both? Also … do I have the order of the farm name and surname correct or in this example is Bölk the surname and Busacker the farm name? IS the farm name passed on to the children or do they revert to the fathers surname? Or perhaps I misunderstand this tradition. Does this practice orignate with primogeniture? Quite confused.

I found your post on German Farm Ancestors “Stand” very interesting. I am interested in the tradition of German “farm names”. I have an early 18th century Pommern farmer ancestor, Ferdinand Friedrich Wilhelm “William” Bölk genannt Busacker, whose mother was Sophia Boelk and father was David Busacker. I’ve been led to believe that when a Prussian man married a woman who inherited farm property that it was customary for the man to adopt the farm name in this context … ” ‘farm name’ genannt surname” (e.g. Bölk genannt Busacker). If my understanding of the tradition is correct, then should a search for the husband’s and wife’s ancestors pursue the farm name, the surname or both? Also … do I have the order of the farm name and surname correct or in this example is Bölk the surname and Busacker the farm name? Is the farm name passed on to the children or do the children revert to the fathers surname? Or perhaps I misunderstand this tradition. Does this practice originate with primogeniture? Quite confused. Any answers, clarifications or references to helpful texts would be appreciated.

mit besten Wuenchen

Steve MilnerChelan, WA USA

Hi Steve,

I am not an expert on farm names myself, but check out these articles:

https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/what-is-a-german-farm-name

https://www.legacytree.com/blog/farm-names-family-history

Hopefully they will shed some light on your questions!

Legacy Tree explained the order of naming very clearly. My ancestor, Ferdinand Friedrich Wilhelm William Bölk genannt Busacker, had Bölk as a farm name and Busacker as his surname. His mother’s name, my third great grandmother, was Sophia Boelk which presents the possibility that she inherited the farm and passed it on to her eldest son who then took the farm name – my second great grandfather William. Thanks Katherine!