*This post contains some affiliate links, which does not affect you at all, but does help support James Beidler’s business as he earns a small amount from qualifying purchases as an Amazon associate.

It’s been said that many historians can avoid being genealogists, but that no genealogist can be effective without also being a historian.

And when the genealogy involves the German-speaking people of Europe, somebody’s going to need a map—well, a lot of maps, actually!—and fortunately many of them have been collected in the new tome I’ve compiled, The Family Tree Historical Atlas of Germany (A note for those who’ve heard and are wondering: Yes, this publisher—Family Tree Books, a division of F+W Media—is going through Chapter 11, but the books are being printed!).

Germany Has Complicated History

The reason for needing this book is that the history of German lands is complicated—and that’s before you hone in on the details! But those details are essential to be able to have a shot at tracking down every last record of your ancestors because it is your German village of origin’s political and church affiliations in the past that likely have an impact on where the records of particular villages are archived today.

This can be somewhat challenging because Germany has what I call a “non-linear” political history. In the United States, new municipalities and counties are generally created from existing entities – a “linear” political history. Germany, on the other hand, was a collection of small, independent states that were constantly being sliced, diced and otherwise disconnected as noble dynasties went extinct, lost wars or were divided amongst sons.

Three Time Periods Crucial

Truthfully, you often need to know at least three of the political and church allegiances for a village: during the era when an ancestor lived there; during the Second Empire period (since those affiliations are found in MeyersGaz.org and the Family History Library Catalog on FamilySearch.org); and today’s boundaries, both to help find villages on the modern map as well as what the current archives are.

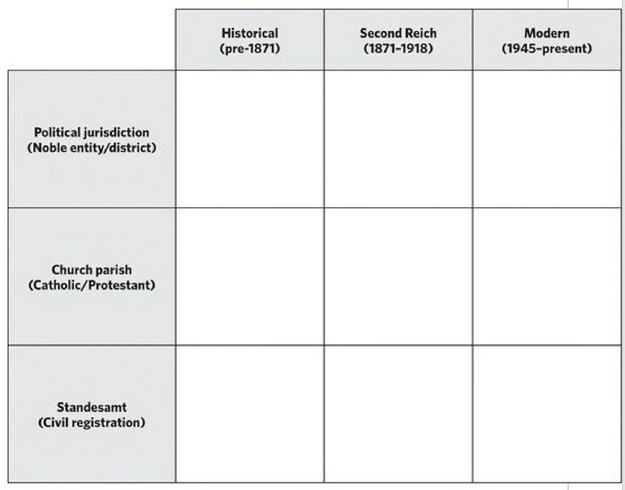

Indeed, researchers should play what I call “Heimat Tic Tac Toe” and create a grid with sites of a village’s political jurisdiction, church parish and civil registry locations.

What’s in the Atlas

This publication brings together more than a hundred maps from Roman times through the present day, with an extra focus on the nineteenth century when peak immigration to America took place. It includes closeup two-page maps of every German state and Prussian province from this period. In addition to the partial index of cities and immigrant hotspots included in the print-version of the atlas, there will be an every-place index available online.

For each area of Germany, there is also at least one detail map for the pre-Napoleonic era to show the smaller states; other chapters include modern-day German state maps, as well as some showing demographics such as religion and dialects and also a few maps showing German-speaking Austria and Switzerland.

History of Germany Included

The book begins with a history highlights section that covers the main themes of German history as they relate to genealogy, including an explanation of how German boundaries became so complicated.

In part because of the German preference for following the Salic Law of partible division (in which all male children get a share of an inheritance), what is today Germany became a crazy quilt of small states. Other causes of disunity included the elective nature of the Emperorship (candidates offered bribes of territories and enhanced status).

In many cases all of the territory of a small state wasn’t contiguous; there abounded many enclaves (a territory, or a part of a territory, that was entirely surrounded by one different state) and exclaves (a portion of a state or territory geographically separated from the main part). It was only during the Napoleonic time period in the early 1800s when many of the small states and all of the religious states (ruled by so-called “Prince-Bishops”) were annexed into larger neighbors; this remained the rule after the defeat of Napoleon, with only the region of Thuringia remaining a spot with many small states.

Case Study: Hessen

Here’s an example of how maps and the political boundaries they show (as well as that historical background knowledge genealogists’ need) can help narrow down the focus of research even when a village of origin isn’t known.

Researcher Melissa Dunkerley has been trying to find the origins of Ernst Scharff, whose birthplace is variously identified as Hesse-Darmstadt and later as Prussia—and sometimes as the entirely unhelpful “Germany.”

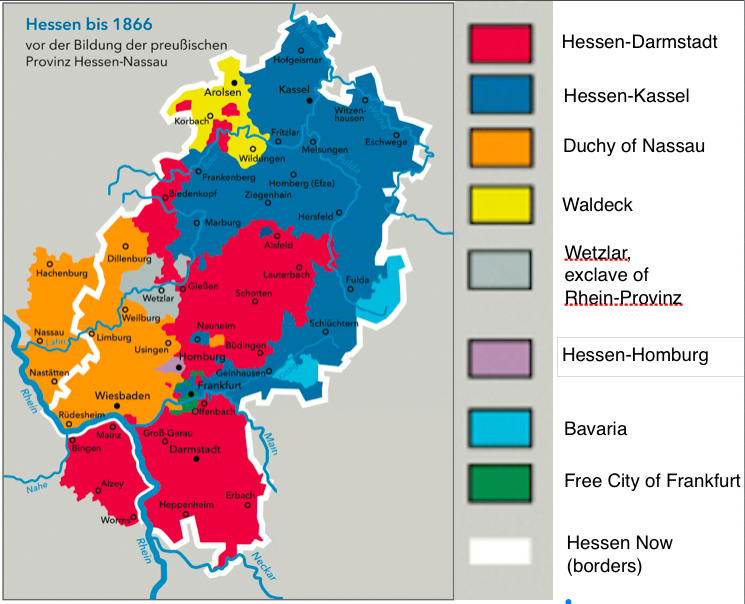

While censuses just can be plain wrong, there’s a map of Hesse (Hessen in German) that gives Dunkerley a decent theory on how to square the circle of these various assertions of Scharff’s birthplace.

The map “Hessen bis 1866” shows the boundaries before they were adjusted by a Prussian land grab that occurred in a war that year. The red boundaries on this map show Hessen-Darmstadt before that war; among the changes as a result was that the thin arm centered on Biedenkopf was ceded to Prussia, making the relatively small number of villages in that “arm” the prime suspects for Scharff’s Heimat, since that would be consistent with him showing Hessen-Darmstadt as his place of birth in records before 1866 and Prussia afterwards.

To Order the Atlas!

The Family Tree Historical Atlas of Germany is available here – get your copy today.

Beidler is a freelance writer and lecturer on genealogy as well as a research-reports editor for Legacy Tree Genealogists. Contact him by e-mail to james@beidler.us. Like him on Facebook (James M. Beidler) and follow him on Twitter, @JamesMBeidler.

2 Responses

Have all your books–very useful, especially the German atlas.

Would this atlas show details relative to the 1660 period?