By Loretta Niebur Walker, Ph.D. and Elizabeth Niebur Lee of Daughters of Jacob Genealogy

We feel like we have hit a gold mine when a client comes to us with the name of a parent’s ancestral town in eastern Europe, especially when it is written in their parent’s own hand. When we discover that the record includes the names, birth dates, and home towns of that parent’s parents and siblings, it is as if the gold mine just became platinum.

Conventional wisdom is that by the time an ancestral town is identified, the hardest work is done—probably because that is often the case. This can be especially true when the family is from the southeastern Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia, for which many indexed records are available on the JRI-Poland and Gesher Galicia websites.

In a document provided to us by our client, her father named his parents as Itzhak Josef Katz of Mikulince, Poland, and his mother as Rose Sara Katz of Tarnopol, Poland, along with the names and birth dates of three siblings, all with the last name Katz. A note added later in another hand indicated that Rose’s maiden name might have been Braun or Garff. In another document that we found early on, for which our client’s father also provided information, he listed his father as Josef Engel, his mother as Rosa Schorr, and his own last permanent address as Mikulince, Poland.

Now, all we had to do was learn if the records from Mikulince and Tarnopol exist, if they are available online, access them, and piece the family together. It was a genealogist’s dream job.

Well, maybe.

A time-lapse video of our search would show us searching in the extensive databases of JRI-Poland, Gesher Galicia, FamilySearch (indexes and images), and the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie (AGAD) for records containing variants of each person’s name, plus any connection to Mikulince or Tarnopol. We found no records that we could be reasonably confident belonged to this family.

Surely, a family of seven, whom we were sure had lived in Mikulince for decades could not be that invisible. Our client’s father watched his parents and siblings be deported from that town. He listed Mikulince as his home town on every document he completed after his arrival in the United States. How is it that there is no record of anyone in his family living in that town? Surely there had to be someone connected to our client’s family, somewhere on the 30-plus pages of small-font results that listed every person who had any of the many names we searched, as well as any connection at all to the town of Mikulince or its environs.

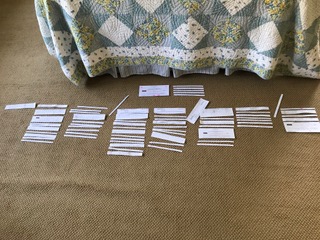

Testing that assumption involved the very low-tech strategy of cutting the lists apart into separate names, and then grouping as many of those names as possible into family groups, using the information given. By doing this, most of the Engels in Mikulince fit into family groups, with comparatively few “orphans” left over. The Katz family names from the same town did not gel into families as well, but to our chagrin, there were no clear connections to our client’s family anywhere.

It was as if all the people in this family were invisible for their entire lives. It is understandable that individual documents for specific people may be missing because of gaps in the available records, or lack of records altogether. However, the odds are very slim that an entire family of seven could live in a town for decades and not have any major life event of any person in that family inscribed anywhere in that town’s well-kept records. Add the fact that we could not find any of the family mentioned in any records within a 50-mile radius, and this case was especially puzzling.

But by this point, I was so deeply invested in these people that I could not let them go. So, I examined all the results of the entire JRI-Poland and Gesher Galicia databases again, giving closer scrutiny to entries to which I had given only passing attention for any of several reasons. Perhaps, the names, dates, or relationships did not fit, or the town in which the recorded event occurred was more than 50 miles away from Mikulince or Tarnopol.

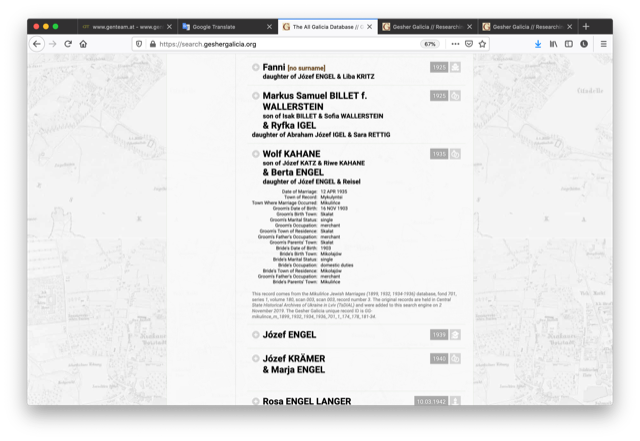

Revisiting the broad search results did not seem much more productive than the previous passes them. However, one long-shot Gesher Galicia indexed record began to stand out.

Unfortunately, we were not able to access an image of the original record from which the indexed information was taken, so all we had to work from was the indexed information. Could this record help us find the elusive Katz/Engel/Schorr/Braun/Garff family? The pros and cons of this record belonging to our client’s family are summarized as follows.

|

Pros |

Cons |

|

Last name: Engel |

First name: Berta, not known in family |

|

Parents: Josef & Reisel (“Rose” in English) |

Parents: no last names, first names are common. |

|

Marriage town: Mikulince |

Bride birth town: Mikołajów, 100 miles away |

|

Bride’s parents’ town: Mikulince |

Brides’s residence: Mikołajów |

The next logical step was to conduct searches for family names in the town of Mikołajów, which we did, using all of the family names. To our astonishment, the searches picked up both indexed records and scanned images for seven children born to Josef Engel of Mikulince and Reisel Schorr of Mikołajów whom our client knew nothing about!

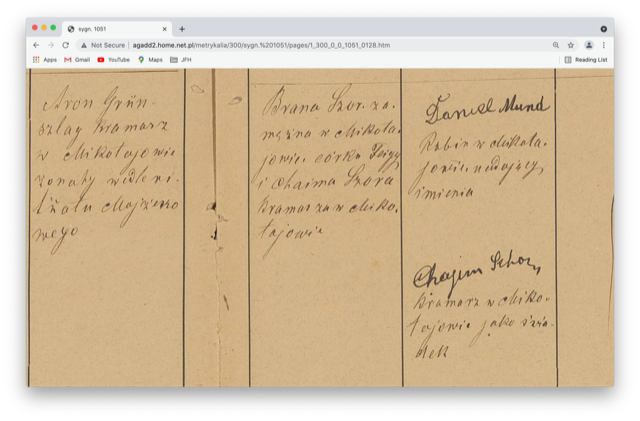

Reviewing these surprising records was a testament to the synergistic power of using both indexed and scanned records in research.

Indexed results make it easy to search for specific names, dates, and locations in a vast body of records, as long as the information is included in the indexed fields of the document. They can also give us a false sense of security that we know everything we need to know about a record and lead us to prematurely trust or distrust a record. This is what happened to me when I first saw Berta Engel’s indexed record. Yet, the broad and deep reach of indexed records is one of the marvels of 21st century genealogy. After all, how else would I have possibly known to search for unknown children in the records of a town 100 miles away from the father’s town, and even farther from the town where we were told that the mother was born?

On the other hand, there is nothing quite like reading the record of an event that was handwritten by someone who probably knew the participants well. Clean computer font cannot capture the feel of the signature of a father attesting to the accuracy of the birth record of his son. Or the signature of a great-grandfather on the birth records of his great-grandchildren when there is no other direct evidence in the records linking him to his descendants. Or reading notes that give updates about an ancestor’s ongoing life— written in the hand of whomever the local scribe was at the time—and reveal insights that we are hard pressed to find in the tidy results generated by search engines.

In all, Berta Engel’s stray marriage record from a distant town led us to nine aunts and uncles of whom our client had never heard, a number of their children, 11 great-aunts and -uncles and their children, plus two more generations of grandparents before that, for a total of nearly 100 people.

A number of intriguing mysteries remain. How did Josef and Reisel meet if their families lived 100 miles apart? Where were they between WWI and WWII when the record goes silent? What happened to the descendants of all of the “new” relatives who have been so recently found? Is the world full of family whom we don’t know yet? I suspect that it is, more than we know.

Acknowledgments

The research in this blog was made possible by the generous efforts of those who support the following websites:

JewishGen. Hub for all things Jewish genealogy. A great place to begin and find advanced information. https://www.jewishgen.org

Gesher Galicia. Detailed indexes of records from within the boundaries of the Austria-Hungary province of Galicia, which now lies in southeastern Poland and western Ukraine. Site accessible through JewishGen. Members have access to additional information. https://search.geshergalicia.org/

JRI-Poland. Jewish Records Indexing of Poland. Less detailed indexing of a vast store of Jewish records from historical boundaries of Poland. Records link to images of original records. Accessible through JewishGen. There is not much overlap between GesherGalicia and JRI-Poland. https://jri-poland.org

FamilySearch. Entirely free genealogy site with vast resources and helps of all kinds. The source for many records that other sites index. Fabulous research helps in their “Research Wikis.” https://www.familysearch.org

AGAD. Central Archives of Ukraine Jewish Records from Communities beyond the Bug River. http://www.agad.gov.pl/inwentarze/Mojz300x.xml.

About the Authors

Daughters of Jacob Genealogy is a boutique family history service that specializes in searching out the roots of clients of Jewish heritage and then bringing their unique family histories to life in gorgeous heirloom books that capture the imaginations of all generations.

For more information, visit https://www.daughtersofjacobgen.com

15 Responses

Very interesting to read your process! And so glad you took a chance on that one indexed record with a match…just goes to show we should never assume anything while doing our research. While in general people didn’t stray far from their place of birth, there are plentifuly examples of those who did. Thanks for a great case study!

You are welcome. Thank you for enjoying our blog. If the lives of the living are full of surprises, it seems that the lives of those who have passed sometimes surprise us more!

Almost all my German ancestors (so far have been from western Germany, and for the most part I find a bride’s family goes back further in the church records than the groom’s family – particularly if he works at a trade, not as a farmer. There have been a couple of long-distance leaps – from one area ruled by a particular noble family to another area ruled by that family. I think there was also one where, IIRC, the ruler changed from a protestant to a Catholic, and my ancestor moved to a protestant state.

The bigger problem for finding church records has been that, just as we do now, people approximated where they were from to a nearby town someone might have heard of. But the records are in a tiny little parish’s register and the parish is just the name of a road on modern maps 🙂

Another problem is there are so many little places with similar names, and if you read the handwriting wrong, you end up looking in completely the wrong place.

Whether or not a family stayed in one place depended a lot on its social and economic status. I have noticed in my research on my maternal ancestors from Pomerania (now part of Poland) that individuals listed as a “Tagelöhner” (day laborer) or at best a “Büdner” (someone who did have a house but owned little or no land so that he had to work on others’ farms) tended to move around more often, probably in search of work. The main village I have studied, Buckowin in Kreis (county) Lauenburg, had 56 inhabitants in the Prussian census of 1871, and only 13 of them had been born in this village. Those 13 probably include most of the 10 children under the age of 10, so most of the adult inhabitants had been born elsewhere. Interestingly, this census data notes that 4 years earlier the village had had 74 inhabitants. I suspect that most of the ones who had moved away had emigrated (mainly to Chicago). Unfortunately the original census returns were lost in World War 2, so only these summaries survive.

Great post.

In my case, cross-references in German city church records led me to a GGGrandmother’s village birthplace and family there.

I have found regional genealogy groups helpful; in this case, the Hessische familiengeschichten Verein.

I looked for 40 years for the direct immigrant ancestor. Found the places of origin of all of the relatives except him.

Where tt was found was in a Compgen database of Prussian police records. He was wanted by them for going bankrupt and fleeing town with his daughter (the wife had passed away already). So, never give up!

Great story. We never know who will show up, where, when or how. 🙂

I love the story! We never know when, where or how we will find those who have eluded us, do we?

I was tickled to see your photo of a cut-up list of names to sort into family groups, because I did that once! I have been trying to find the birth record of one of my great-great-grandmothers, starting with a name, birth date, and town (written down by my family). Margaretha Ulherr was born in Leinburg, Bayern. But when I looked at the parish books for Leinburg on Archion, there were LOTS of Ulherrs with large families living there, with common first names and many had the same profession for several generations.

I recorded what I could find on a spreadsheet that was too unwieldy to really start moving individual record lines around without making a mess of the project. So I printed it out and cut out the individual record lines and spread them on the floor to try to figure out the family groups. I thought at the time I was the only crazy person to do this! I was able to make good progress in matching up family members.

Unfortunately, I never did find a birth record for a Margaretha that matched the date written down by family, and I eventually had to move on to other research out of frustration. I started to suspect that maybe she was born in another town, for some reason. It’s still a project I’d like to get back to (if I can make sense of where I left off)!

No, you’re not the only crazy person. I did that very thing some 30 years ago to sort out what turned out to be 4 or 5 different branches of one family name, after they were living in Ohio. Worked marvelously. Same family name back in Germany is now giving me fits trying to fit even more of the same first names into different branches. Am grateful for Archion, as it did help me trace back 2 more generations, but as in this blog, they were from a different church/village in the records. Still looking for the birth of my great-grandmother. Her parents were married 2+ years after the many-times same recorded date of her birth (tombstone, too). No record of her (possibly) illegitimate birth, no record of her parents having a relationship before their marriage, have DNA connections to 5 of the 7 of her siblings (all well-documented in the records in Germany as from the parents), and one brother was living with her and her husband in the same house after arrival in Ohio. Have branched out to other localities, but cannot find even one female born on that date, let alone in that family, as I am thinking maybe NPE, and she was “adopted”. But, then there’s the DNA connections. NPE from relative? The search goes on!

I’m happy to join you in the Crazy People with Paper and Scissors Club. 🙂 Occasionally there is nothing quite like moving physical pieces of paper around.

As for unsolved mysteries, I have an unwieldy file of just such names, sorted into envelopes, awaiting their turn to be spread out on the floor again, perhaps after more records become more readily available. 🙂 Best wishes.

I have been SOOOO stuck trying to find my relatives in Germany and Poland. Their immigration records list Liebemuhl and Saalfeld Prussia as hometowns but trying to find any records is proving fruitless. Nothing seems to fit. Thank you for your article- it gives me hope 😀

The nature of hope is that its validation lies over a horizon, beyond which we cannot see. Keep hoping and working on.

This is an amazing story and one that I suspect I will need to repeat as my research goes beyond the ‘easy’ records. My one question: What information in the key record made it stand out to you as the one to be pursued? Curiously, I wonder if you also pursued several other similarly-likely records before concluding that this one was the key? Thanks so much.

Good questions. Yes, I did look at other outlying records, as well. In fact, I looked briefly at this one a few times and passed it over as unlikely–but my genuine answer that is neither traditionally scientific not in the realm of linear logic answer is that when I have a quiet, nagging feeling that something is either right or wrong, I look into it more carefully. It doesn’t hurt to look in the wrong place (or lots of wrong places) and what a treasure it is when that feeling leads us to a right place! Even scientists and mathematicians trust their gut along with their methods more often than is generally acknowledged. It is no different in genealogy. Of course, we want to verify our work with solid methodology, but there is room for both kinds of input in our work. The results are worth it.