As a former language teacher, I know that the listener’s or reader’s understanding of what I am saying or writing is very contingent upon him/her having some context about the language I am producing. In other words, if I am telling a story about an apple, showing a picture of the fruit helps to create a context and enhance understanding.

Similarly, if I am telling a story about an apple and show a picture of a banana, I have created a very misleading context for you to understand my story and you likely won’t gain anything from my narrative.

So, what does context have to do with reading and understanding German genealogical records? A lot!

If we are fortunate enough to find old German church records written in a columnar format, the context is very clearly created. The columns are all labeled and we know exactly the type of information that will be found in each block below the column header, such as a date, the first name of the father, the name of the groom or bride, etc. Similarly, from the preprinted forms found in the records from the Standesamt (civil registry office), we know exactly what type of information will follow in the provided blank. The context is created and we stand a better chance of getting to the information we seek, in spite of the sometimes very elusive Kurrentschrift.

But what happens if our context is faulty as with the apple and the banana?

In that case, we end up not gathering the information we were hoping to find.

A friend of mine, who is the daughter of an early 20th century German immigrant, asked me to decipher some old German church records that a family friend in the old country had sent her. She told me that they come from a Lutheran church in the state of Hessen and date back to the 1730’s or earlier. So, my thinking was that Martin Luther translated the Bible into German to allow all Germans to hear the word of God and therefore, records from a church he founded would be in German.

But unfortunately, as you will discover, my context was extremely flawed.

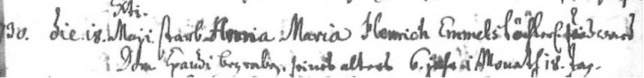

The very first record she provided is a burial record for a young girl

- die 18. Maÿ starb Anna Maria Henrich Emmels Töchterlein und ward

Dom. Exaudi begraben. Seines alters 6. Jahr 4(?) Monath 18 Tag.

When the Words Seem Incorrect…

My first clue that something was amiss was the very first word in the record: die. First year German students learn that dates begin with the masculine accusative form of ‘the:’ den.

Although I lived in Hessen as a student many years ago, I never heard a native German use the incorrect form of ‘the’ with a date, but I thought that maybe it was something about the dialect that I didn’t know.

The second clue that something was wrong came with the use of the word Dom. In German, that is a cathedral and that is not a term that would readily be used to name a Lutheran religious structure. But my thinking was that the child was buried in the church cemetery, although the preposition ‘in’ was blatantly missing from the phrase.

When the Letters Don’t Make Sense…

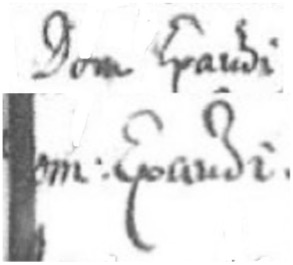

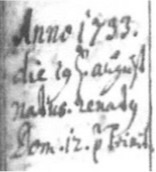

That brings me to my next faux pas. The word after Dom is Exaudi, but for longest time I thought the second letter was a ‘p’ not an ‘x’. Sadly, my context was driven by having learned penmanship in an American school, not a German one! The letter ‘x’ is used in so few German words, that it never crossed my mind that it was anything other than a ‘p’. The mystery phrase also showed up in other records on the initial documents I was provided, as shown here in the composite:

Additional Records to the Rescue

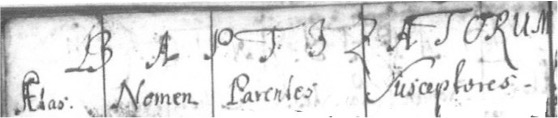

It wasn’t until my friend sent this additional record that it finally hit me that my context was very flawed!

This is a baptism record from the same Lutheran church, and the name of the page as well as the headings were in Latin – not German! My initial context finally got slapped into reality and what I was looking at in the burial record of the youngster was mostly in German, with a smattering of Latin included as well.

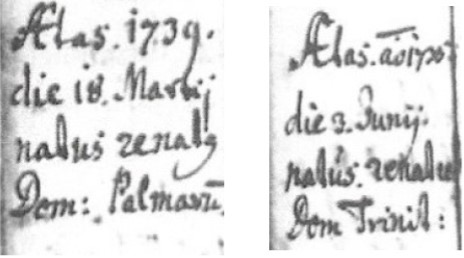

But it was an entry from this baptismal record that finally totally corrected my initial faulty thinking.

It All Starts to Make Sense

The above entry comes from the first column to the left, the date of the baptism. Again, the beginning of the date is the word die, but it was the last line of this entry that finally made me realize with what I was dealing. The phrase 12. p. Trinit brought back memories of catechetical training as a teenager that each Sunday in the liturgical year has a name and I obviously recognized the word Trinit as the word Trinity. While I have no formal training in Latin, I did recognize p. as the abbreviation for post, after. So, obviously the word Dom is the Latin word for Sunday, and this particular baptism took place on the 12th Sunday after Trinity.

Other records helped to solidify my thinking and I now knew that I was dealing with German Lutheran records with lots of Latin!

These two baptisms took place on Palm Sunday and Trinity Sunday itself.

Website Help

However, I still had no idea what Epaudi, or correctly, Exaudi Sunday was, until I did a little web surfing and came upon a very useful site that provides insight into all the Latin words used in the liturgical calendar as well as other useful Latin words and phrases, such as the months of the year and numbers.

Latin Language and Script: Resources for the Genealogist

Dates and the Liturgical Calendar in Latin

http://sites.rootsweb.com/~chevaud/latin_liturgical_calendar.htm

It was from this site that I finally learned that the word was Exaudi, not Epaudi and it is the Sunday after the Ascension, about 42 days after Easter.

Another useful source of Latin words and phrases found in church records is located on the FamilySearch website:

It was on this website that I discovered that die is the Latin word for ‘day’ and that natus and nata mean ‘born’ (male/female) and renatus/renata mean ‘baptized.’ Ætas is the Latin word for ‘age’ or ‘date’ and obviously Anno is year.

Unfortunately, I had not yet purchased Katherine Schober’s latest book: The Magic of German Church Records. If I had had that book on my shelf, I would have been able to dispel my faulty context much earlier and my work with my friend’s records would have proceeded much more smoothly!

Needless to say, I created a very faulty context in dealing with my friend’s records and it took some time, energy and research to undo my initial thinking! (It might have helped had I studied Latin in high school or college, but my language studies were focused on modern tongues: German, Russian, Spanish, and Dutch!) But in addition to making sure that I don’t jump to a flawed context, I learned that in genealogy work if you think you’ve seen it all, you probably haven’t!