While learning German is obviously not required for German genealogy research*, it often helps to have at least a bit of understanding of the language when looking for your ancestors. In addition to being able to recognize the most important genealogy words in German records, knowing a little about how the German language works can help you to narrow down what documents you think are important for your genealogy research. Below, I have summarized some of the most basic facts about the German language, in the hopes that this may give you a bit of a leg up when looking at your German documents.

*If you want to learn to translate your German records yourself – with the exact German you need for genealogy – check out our newest course German for Genealogists.

1. All nouns are capitalized.

In the German language, all nouns (persons, places and things) are capitalized, no matter if it is a “proper noun” or not. For example, the word birth (Geburt) is capitalized in German, as is the word child (Kind). So if you see a capital letter, you now know that it does not necessarily mean that the word is a name – it’s likely just a noun.

The word Geburt (birth) is written with a capital “G”.

2. German has many different words for the word the.

Crazy, right? Depending if the word is the subject (Nom), direct object (Akk), indirect object (Dat), or possessive (Gen)*, the German word for the changes. No need to worry about what these grammatical terms mean for this article (unless you are a grammar nerd like myself – in that case, see below), but if you see any of the words above, you will know they all mean the.

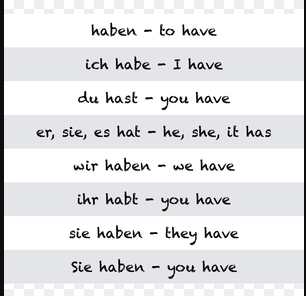

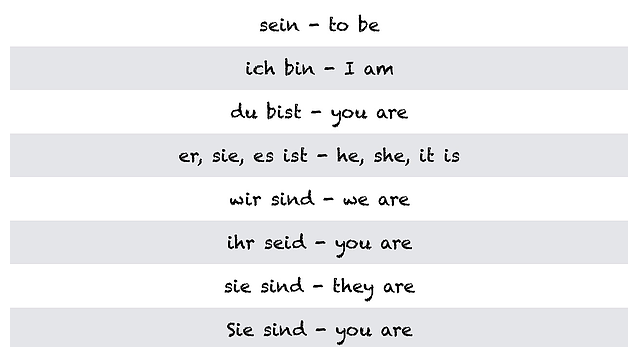

3. Lowercase words starting with ge- are likely past tense words.

The German past tense is formed with either haben/sein (to have or to be – see how they conjugate below) + the past tense of the verb, which is usually formed with ge-. For example, the German word for to eat is essen. To say I ate, you would say Ich habe gegessen. The German word for to drive is fahren. To say I drove, you would say Ich bin gefahren.

Some verbs use a “t” form in their past tense instead of the “-en” ending. For instance, the word for to play is spielen in German, with the past tense (I played) written as Ich habe gespielt. While getting into all the rules of the past tense here would take a bit too long, the important idea to take away is that if you see haben or sein plus ge-verb, the sentence is likely in past tense.

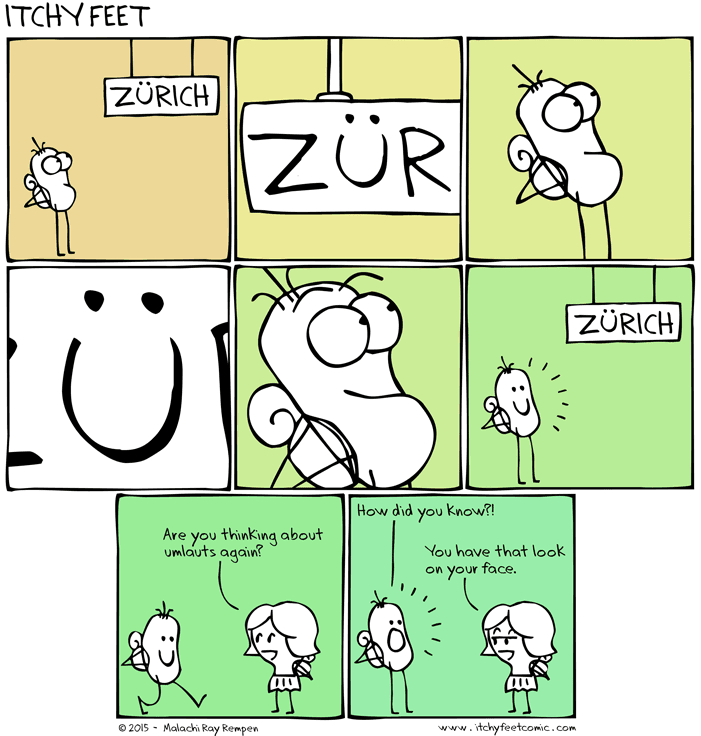

4. Umlauts can also be written out with an “e” after the vowel.

Most German writers do use the umlaut (ä, ö or ü), but in some texts, you will see this sound written as ae, oe and ue instead. In genealogy, this is especially relevant for the spelling of certain last names. For instance, the last name Mueller is spelled M-u-e-l-l-e-r in America, but our German ancestors spelled it M-ü-l-l-e-r. The ü changed to a ue in English spelling.

5. German loves compound words.

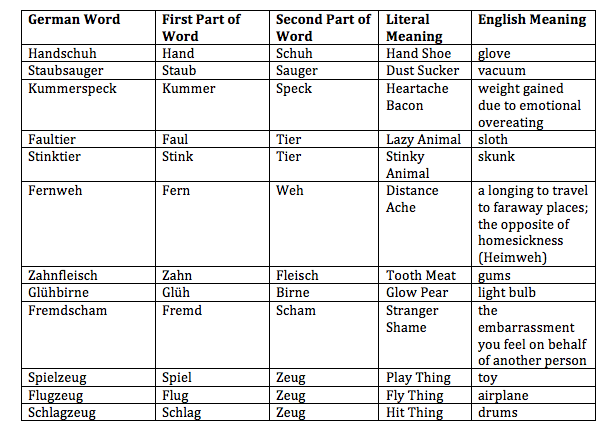

The German language consists of many compound words, or two words combined together to form one. How does this help you? Well, if you come across a word and can’t find it in your dictionary, try looking up the two parts of the word individually. This should then help you to form a better idea of what the author could have meant.

Some fun examples of German compound words include:

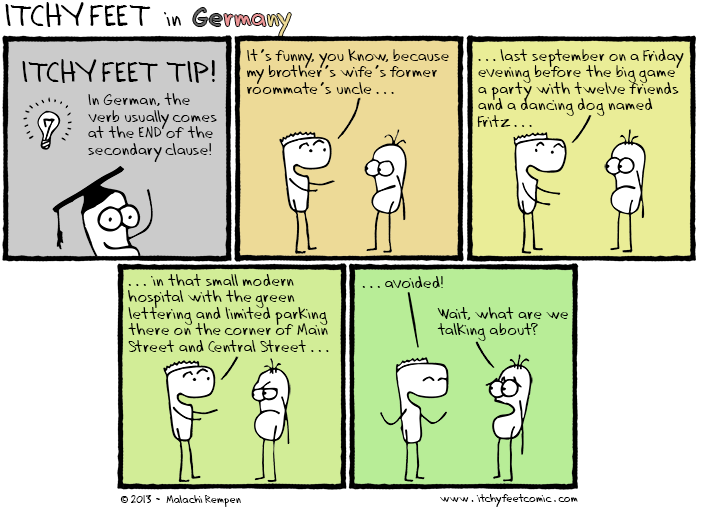

6. Sometimes the verb is written at the very end of the sentence.

While many German sentences do use Subject-Verb-Object word order (just like we do in English: “I ate the burger”, in which the verb, ate, comes right after the subject, I), sometimes German puts the verb at the very end of a sentence or phrase. Why would they do such a crazy thing, you ask? Well, if the sentence includes a certain type of word (a subordinating conjunction*, to be exact), such as weil (because), dass (that), ob (whether), während (during), etc., this is a signal for the verb to move to the end of a sentence, as it cannot be directly after the subject when one of these words are present. So if you don’t see the verb after the subject, keep reading, and it may be the very last word in the sentence. See this article on German word order for more information: https://www.fluentu.com/blog/german/learn-german-word-order/.

Mark Twain explains this crazy grammar best in his article “The Awful German Language“:

“An average sentence, in a German newspaper, is a sublime and impressive curiosity; it occupies a quarter of a column; it contains all the ten parts of speech — not in regular order, but mixed; it is built mainly of compound words constructed by the writer on the spot, and not to be found in any dictionary — six or seven words compacted into one, without joint or seam — that is, without hyphens; it treats of fourteen or fifteen different subjects, each inclosed in a parenthesis of its own, with here and there extra parentheses which reinclose three or four of the minor parentheses, making pens within pens: finally, all the parentheses and reparentheses are massed together between a couple of king-parentheses, one of which is placed in the first line of the majestic sentence and the other in the middle of the last line of it — after which comes the VERB, and you find out for the first time what the man has been talking about; and after the verb — merely by way of ornament, as far as I can make out — the writer shovels in “haben sind gewesen gehabt haben geworden sein,” or words to that effect, and the monument is finished. I suppose that this closing hurrah is in the nature of the flourish to a man’s signature — not necessary, but pretty. German books are easy enough to read when you hold them before the looking-glass or stand on your head — so as to reverse the construction — but I think that to learn to read and understand a German newspaper is a thing which must always remain an impossibility to a foreigner.”

You can see what Mark Twain means in this newspaper article I had the pleasure of translating below. The subject of the sentence, Termin (appointment), is in the second line, while the verb festgesetzt (was set) doesn’t appear until 9 lines later! So if you can’t find the verb in your document, don’t give up – just read on for a few more hours and it may eventually appear.

While there are of course many more intricacies to the German language – check out the German for Genealogists Course if you’d like to learn more -, it is my hope that these basic tips will give you a bit more of an idea of how German works. The German language is at times fascinating, at times entertaining, and yes, as Mark Twain put it, at times awful – but overall, it is a great language to know, especially if you’re researching your German genealogy. Until next time, auf Wiedersehen (which happens to be another great compound word: wieder means again, sehen means to see)!

Image Credit: www.itchyfeetcomic.com

* Cases in German, explained with English examples:

Example Sentence: The girl threw me the ball.

Nominative case is the subject, which answers the question “who is doing the action?”.

Who threw the ball? The girl. Girl is therefore the subject of the sentence.

Accusative case is the direct object, which answers the question “who or what after the verb?”. The girl threw what? The ball. Ball is therefore the direct object of the sentence and in the accusative case.

Dative case is the indirect object, which answers the question “to whom or for whom after the verb?”.

The girl threw the ball to whom? To me. Me is therefore the indirect object of the sentence and in the dative case.

Genitive case in German is the possessive case, expressed as “The sister of my father….”

Of my father would be in the genitive case in German.

*Subordinating conjunction: http://grammar.yourdictionary.com/parts-of-speech/conjunctions/subordinating-conjunctions.html

4 Responses

I enjoyed your article, especially wrt compound words since my pre-anglicized family surname is Handschuh.

Thanks

Dwight Hanshew

Thanks Dwight. I love the anglicized spelling of Handschuh!

Loved the comic strip about the verb at the end of the sentence. As I’ve tried to re-learn my high school and college German, I’ve really been struck how you don’t know what’s going on in a sentence until you get to the verb! Also, the section about cases in German is helpful.

I know, it’s so crazy with those verbs! Happy to hear that the case section was helpful!