“Did great-great-great grandfather Conrad Renzel leave behind any of his recipes?” my son Michael asked hopefully. I had just been telling Michael all about Conrad’s start as a penniless immigrant German baker in 1860s San Jose, California. I continued the story with how Conrad had worked hard, first as an itinerant baker selling his goods from a horse cart, then as a bakery and grocery store owner that had started the Renzel family on a path to prosperity. Michael himself is no slouch in the baking department and is always interested in trying new and different recipes. Baking up an antique confection that his 3X great grandfather Conrad might have sold off the back of his horse cart is squarely in Michael’s bakehouse. “Sadly, no,” I answered with a sigh. “Conrad did not leave behind any recipes that I know of.”

But I was mistaken…

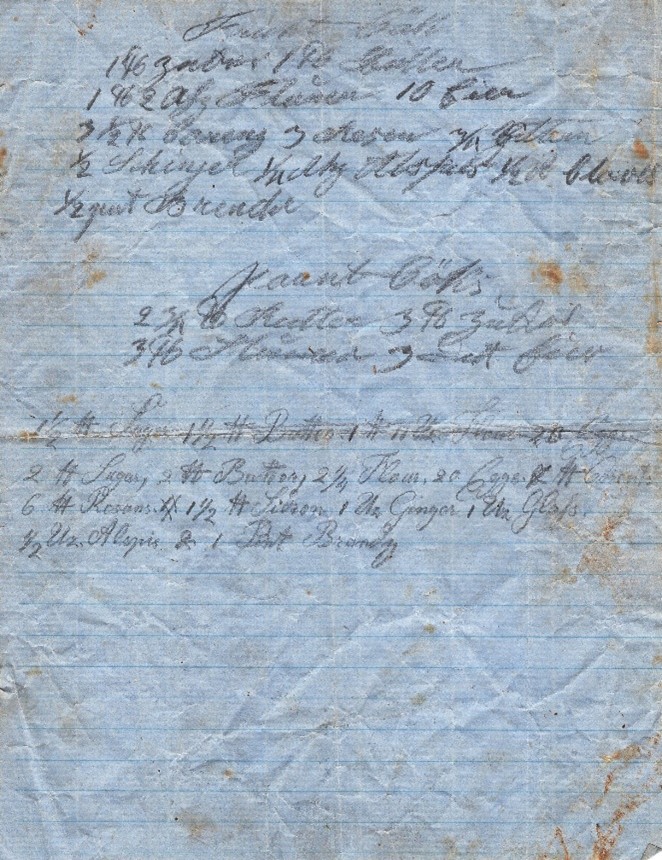

About two weeks later, I found the sheet. It was in an old folder my mom’s cousin Mary Renzel had given me about a decade ago, tucked between a handful of thin yellowed onionskin letters sent to Conrad, and their handwritten translations. The aged paper was blue and lined. On it, scrawled in pencil in faded German handwriting, was what looked like two recipes written in three sections. The paper was stained on the edges with what appeared to be dried batter. Batter stains are always a good sign. It means the recipe was well used and therefore worth making.

Could I bake this 150-year-old recipe?

I thought to myself, “How cool would it be to bake up one of Conrad Renzel’s recipes, about 150 years later?” But first, I had to decipher it!

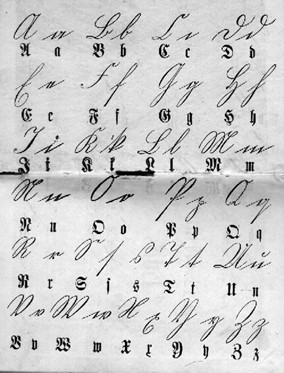

So I set to work to translate the recipe into modern English and modern cooking measurements. I confidently armed myself with my usual tools for such a translation – my German handwriting key, which showed me how old German letters were shaped, my iPhone Translate app, a year of college German taken 35 years ago, and the secure knowledge that there are only so many baking ingredients with sugar, butter, flour and eggs being the most common. My plan was to figure out one word at a time, letter-by-letter, using my German handwriting key, then put the word into the Translate app to get the English name or ingredient. This translation strategy was one that had worked for me before for simple German documents. Surely, this sparsely worded recipe would be a cakewalk to translate by this method too.

But it wasn’t as easy as that…

Well, my strategy did not go as planned from the very start. I began at the top of the page with the two-word title of the first recipe. Strictly matching the shape of the letters with my German handwriting key, I got T-R-U-H-T, Truht—which translates to nothing, zilch, nada, Nichts, in German. “Okay,” I thought, “move on and maybe it will become clearer later what the first title word is.” I looked at the second word of the title. Hmm, that first letter does not look like anything on my German handwriting key. Okay, I decided to move on to the ingredient list and come back to the title later. (Note from Katherine: This is a great method to working with the handwriting. See 5 Transcription Tips for When You’re Just Stuck for more!)

I read the symbols for the first ingredient. It began with the number ‘1’ followed by some kind of symbol, Ꙓ, that in German handwriting looked like a backwards P followed by a little b, then Z-U-C-K-E-R. Knowing the symbol represented a measurement and was repeated for several ingredients, I pretty easily realized the symbol must be the German abbreviation for pound and indeed was very similar to the English abbreviation for pound of L-b. Pounds made sense because as a baker’s apprentice in Hameln, Germany around 1844, Conrad would have been taught to weigh his ingredients. I also confirmed that the metric system was not adopted widely in Germany until 1872. This was well after Conrad came to America, where even today we Americans still stoically weigh things in irrational pounds, instead of orderly kilograms, just to prove we can. And so, what was that 1 lb of? Z-U-C-K-E-R – Zucker; I didn’t even have to look this one up. I remembered Zucker from college. It is sugar. Sweet. I was off to a good start with the ingredient list.

I moved on to the second ingredient: 1 lb. B-U-T-T-E-R, the letter shapes exactly matching my German handwriting key. I paused. Butter, as in butter? I put Butter into the Translate App. Yes, Butter in German is butter in English. Now we are cooking with gas! The remaining ingredients will be easy, I thought smugly, cracking my eggs before they hatched.

I whisked ahead to the third ingredient. I applied my letter-by-letter technique to it and got 1 lb. and 2 Somethings of F-L-A-V-O-R? I used the German handwriting key to spell out the Somethings. A-H-Z—Ahz? “Well, it must be a measurement,” I thought. It’s 1 lb. and 2 Ahz. Then suddenly, as with pound, I had an Ahz-Ha moment and saw it. Ahz is the German abbreviation for Ounces or in English abbreviated O-z. Of course, pounds and ounces. Because why have something easy like 1000 grams in a kilogram when you can have a much more difficult subdivision like 16 ounces in a pound? But I digress.

So now I had the third measurement, but what was the third ingredient? It was here my translation progress started to collapse like a bad soufflé. It was 1 lb. 2 Oz of what? F-L-A-V-O-R —Flavor? “No, that can’t be right,” I thought. Firstly, Conrad would not have used over a pound of FLAVOR and, secondly, FLAVOR is not a German word. I looked again at the inscrutable German handwriting on the sheet. Is that a batter splatter above the V or an umlaut (two dots)? And if it is an umlaut, that cannot be a V! I reconsider the letter shapes in light of the potential umlaut, which only appears above the vowels a, o, and u, and try again. Gee, it almost looks like F-L-A-U-E-R, Flauer. But how could the German word be so literal for the English word, flour? “Well,” I thought, “it was literally the same word for butter, so why not for flour?” So, I used the Translate app to check and the German word for flour is Mehl, like cornmeal, and most definitely not Flauer! What was going on?

My translation efforts really took a sour turn from here, as each successive ingredient became more and more strange and inedible. I looked at the fourth ingredient, 10 Fier, which translates as no German word Apple or Google ever heard of. Then came, or so they appeared to me, the ingredients 3-1/2 lb. barneys, 3 ekeson, ¾ Sittern or Gittern or possibly Bittern, then came ½ Schinfer, ¼ oz tloseo, ½ oz bluves and finally ½ gait Krendie. Try as I might with the iPhone app, none of these latter batter ingredients translated into anything remotely comprehensible in English. It was stuff and nonsense in English. It was Stuss und Blödsinn in German. But what it was most definitely not was a recipe.

A little English help….or not….

I scanned the two other sections on the page for clues. It was then I saw that the third section was not a recipe at all, but an English translation of the ingredients of the first two recipes. Perhaps one of Conrad’s American-born children wrote it, or perhaps it was by an English-speaking assistant working in the bakery. The English translation was still hard to read, the scrawl factor of English handwriting being similar to that of the German. Nonetheless, it served as a Culinary Rosetta Stone to translate Conrad’s two recipes.

As I compared the German ingredients to the English counterparts, I had another Ahz-Ha moment that unlocked the whole thing. The key was this. Conrad did not write these two recipes in Ger-MAN. Conrad wrote them in Germ-LISH! I define Germlish as a mix between German and English handwriting styles and word usage. When read in German, the recipes were just so much Stuss and nonsense. Ah, but in Germlish, they became priceless family treasures handed down five generations!

So why did Conrad write these recipes in Germlish and not in plain German? I have to guess that because Conrad had been in the United States a decade or two or three when he wrote down these recipes, both his handwriting and his word usage had simply become a mix of his native tongue and the language of his adopted country. Hence, after so long, he wrote, and possibly spoke, in Germlish.

The code is broken…

So now I had the secret sauce I was lacking up to this point. Namely, that to translate from German/Germlish to English, I had to look at both the individual letters and the whole word and consider them in both German and English to see what made the most sense. I returned to the top of the page and looked again at the title of the first recipe. When the shape of the first letter was taken as an English F instead of a German T, the mysterious Truht became Frucht, or fruit in English. And the first letter of the second title word that was non-existent on the German handwriting key looks exactly like a capital C in Germlish. The C is followed by an ä and then a k, and with a phonetic German pronunciation, it is Cäk, as in the English word cake! Although the German word for cake is Kuchen, Conrad chose to title his cake using Germlish, so the title is Frucht Cäk – Fruitcake!

We have a cake…

I must confess, upon figuring out that the recipe was a fruitcake, my first thought was, “Conrad left us but two recipes and one of them is a fruitcake!?” But as I looked into the dubious history of fruitcake, it turns out it has gotten a bad rap. Historically, properly made fruitcake such as Conrad’s Frucht Cäk was a welcome and perfectly respectable holiday gift to bring to your in-laws’ house on Christmas Eve or Boxing Day. Fruitcake started to get a bad rap in the 1970s when low quality fruitcakes were mass produced and Johnny Carson started making fun of them on late night TV. Apparently, when made at home or by a bakery with quality ingredients, it was an entirely different and enjoyable piece of cake.

So now equipped with all my usual tools plus the knowledge I was translating from Germlish, not German, the remaining translation became the cakewalk, or rather the fruitcake walk, I had originally envisioned. So here is the fruitcake recipe, in Germlish, with English translation in parentheses.

The 150-Year-Old Recipe:

Conrad Renzel’s Frucht Cäk:

- 1 Ꙓ (lb) Zucker (sugar)

- 1 Ꙓ (lb) Butter (butter)

- 1 Ꙓ (lb) 2 Ahz (oz) Flaüer (flour)

- 10 Eier (eggs)

- 3-1/2 Ꙓ (lb) Beerenz (currants)

- 3 Ꙓ (lb) Resons (raisins)

- ¾ Bittern (bitters)

- ½ Ahz (oz) Schinyer (ginger)

- ¼ Ahz (oz) Glosses (Gloss) [I think this is more brandy brushed on after baking to “age” the cake]

- ½ Ahz (oz) Cloves (cloves)

- ½ pint Brendie (brandy)

Plus one more…

And what is that second recipe on the sheet? As strict German letters, its title looked to me as Saunt or Sarnt or Sanut bëks, all nonsense in German. But I could tell right away from the ingredient list it was a straight up Pound Cake—about 1 pound each butter, sugar, flour, and eggs. Standard pound cake recipes use the same proportions today. On the one hand, I am disappointed that this is not another Conrad original recipe. On the other hand, it is kind of fun to know that Conrad is part of the long history of the Pound Cake, which according to Wikipedia originated in northern Europe in the 1700s. So, when I retranslated the title of the second recipe from Germlish, instead of from German, I got Pount Cäk, a homophone for the English Pound Cake. Pount is not a proper word in German, but it is in Germlish! (Note from Katherine: D and T are often switched in German spelling, as they sound the same to German ears! See Think Like a German: Spelling Variations in Genealogy Documents for more info)

Neither the Frucht nor the Pount Cäk recipes had instructions. They were simply lists of ingredients. As a professional baker, Conrad knew what to do without instructions. And the quantities were for making many fruitcakes and pound cakes at once, not just one. In a companion recipe called The Frucht Cäk of Conrad Renzel (c. 1870), I scaled down the ingredients to make one cake and added instructions.

And now we bake!

So that is the story of Translating the Fruitcake. As of this writing, I am in the process of making Conrad’s Frucht Cäk. There is a two-week aging process where the baked cake marinates in brandy, and I have one more week to go. I have so far resisted the temptation to nibble the cake before the full two-week aging process is up. I want to experience the cake in its full brandied glory, how it would have tasted had I bought it from Conrad’s bakery at 343 South First Street in December 1870 to serve at a holiday gathering. Who knows, maybe baking and eating Conrad’s Frucht Cäk, whether in Germlish or in English, will become a new holiday tradition that will be passed down to future generations well into the 21st century. I hope so. That idea is delicious in any language.