Guest Post by Sean Daly, U.S. Community Manager at Geneanet

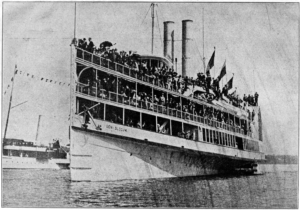

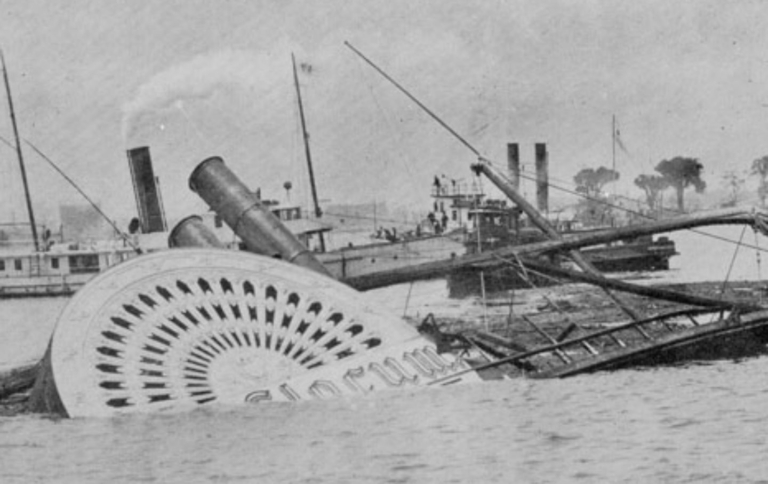

On the morning of June 15, 1904, in New York’s East River, the paddle steamer General Slocum caught fire heading into Hell Gate and burned as the captain frantically raced to a beach at North Brother Island. Some 1400 passengers were aboard, mostly German-American women and children celebrating the end of St. Mark’s Lutheran Church’s Sunday school classes. It was a Wednesday, so fathers and husbands were at work while the excursionists had looked forward to a fun picnic day on Long Island. Over a thousand of the passengers lost their lives that day, most drowning as they jumped to escape the inferno, some only yards from the shore as the blazing ship beached. It was New York City’s worst disaster until September 11, 2001.

Could It Have Been Prevented?

Like many disastrous events, there were a number of factors which formed a chain while any broken link could have prevented or mitigated the catastrophe and its aftermath. A cabin was used for storage of inflammable materials, against regulations. The crew had never been trained in firefighting – some had in fact never worked on a boat weeks before – and the security equipment (hoses, life vests) was defective, yet had been certified as inspected and in good condition by an inept or corrupt federal inspector. An accurate count of passengers was not made; even today, no two lists are alike. The captain was warned of the fire in its first moments by a boy of twelve; he was gruffly chased away as a prankster. The crewman who discovered the fire lost precious moments when the fire could have been contained. The thirteen-year-old wooden ship had been repainted many times with flammable paint; the lifeboats were painted to the deck; there were no steel bulkheads to contain the fire; the sliding doors amidships which could have slowed the fire’s spread wouldn’t close.

In the Hell Gate strait, the captain had a flood tide pushing from behind while a headwind fanned the flames aft; he couldn’t turn the boat east to the shore because of the rocks and currents, nor could he turn west as shallows there were full of rocks. So full speed ahead he charged towards the Bronx as passengers jumped or fell, barely any able to swim, weighed down with their Sunday clothes, wearing worthless life vests, some of which were weighed down with hidden metal bars meant to be passed off as having the required weight. Tugboats raced to the scene to save the drowning; some captains and their crews were singed from the intense heat as they took dozens of people off. Mothers were unable to gather or protect their children. That one day, entire families were wiped out.

The disaster had a major impact on Kleindeutschland – Little Germany – the heart of New York’s German community on the Lower East Side. As news of the awful horror arrived, followed by a few drenched and dazed survivors who had ridden the El down from the Bronx, fathers rushed about telling each other that something terrible had happened.

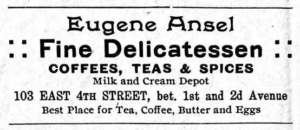

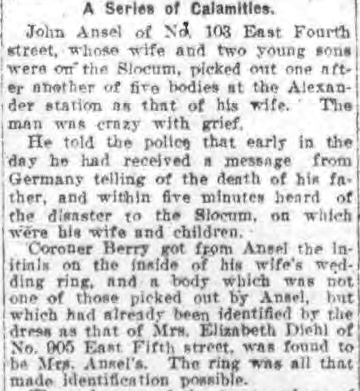

Eugene Ansel, called Gene by everyone, operated a popular delicatessen at 103 East Fourth St. On that quiet morning, a telegram delivery boy had just brought dreadful news: his father Louis, a woodcutter in the small village of Wasserbourg in the Vosges mountains of Alsace, had just died. Eugene, who had arrived in New York twelve years before, would never see his father again. Minutes later, a friend burst into the shop and, seeing Eugene’s face, started telling him what he knew of the steamboat disaster. It took Eugene some moments to understand that this would be the worst day of his life: his wife Louise, 28, and sons Eugene, 5, and Alfred, 3, were aboard the Slocum.

About Eugene:

It seems Eugene always told everyone he was from Guebwiller, a town in Alsace nestled in a valley at the southeastern edge of the Vosges. No doubt he knew of the town from a young age, down the valley from his native Wasserbourg. Perhaps it was in Guebwiller he learned to cook? He was only 20 when he arrived in New York in 1892, but five years later, when he married Maria Louise Gemberlé, he was already cooking in New York hotels. Louise, as she was called, was from Guebwiller herself. Did Eugene send for her?

Alsace and Genealogy Research:

Alsace is a particularly challenging region for genealogy research. Wellspring of the House of Habsburg – the Holy Roman Empire in Vienna – a dialect of German is still spoken there and Alsace has long considered itself separate from Germany. In the mid-17th century, the Peace of Westphalia added the lands west of the Rhine to France and promoted the peaceful coexistence of Catholics, Protestants, and Jews. The province has changed hands between France and Germany several times: in 1871 (the Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen following the Franco-Prussian War), in 1919 (the Treaty of Versailles which returned Alsace and Lorraine to France), in 1940 when Alsace was annexed to Germany (with young Alsatian men drafted into the Wehrmacht, the “malgré-nous”), and in 1945 at the end of the war. Record keeping has been reliable since the Napoleonic Code was introduced in the early 19th century, but these changes mean that birth, marriage, and death records can be found in either French or German. The marriage of Eugene Ansel’s parents was recorded in French in 1866 (left), while his birth in 1872 was recorded in German (center), as was his future wife Louise’s birth in 1876 (right).

Back to the Slocum Disaster:

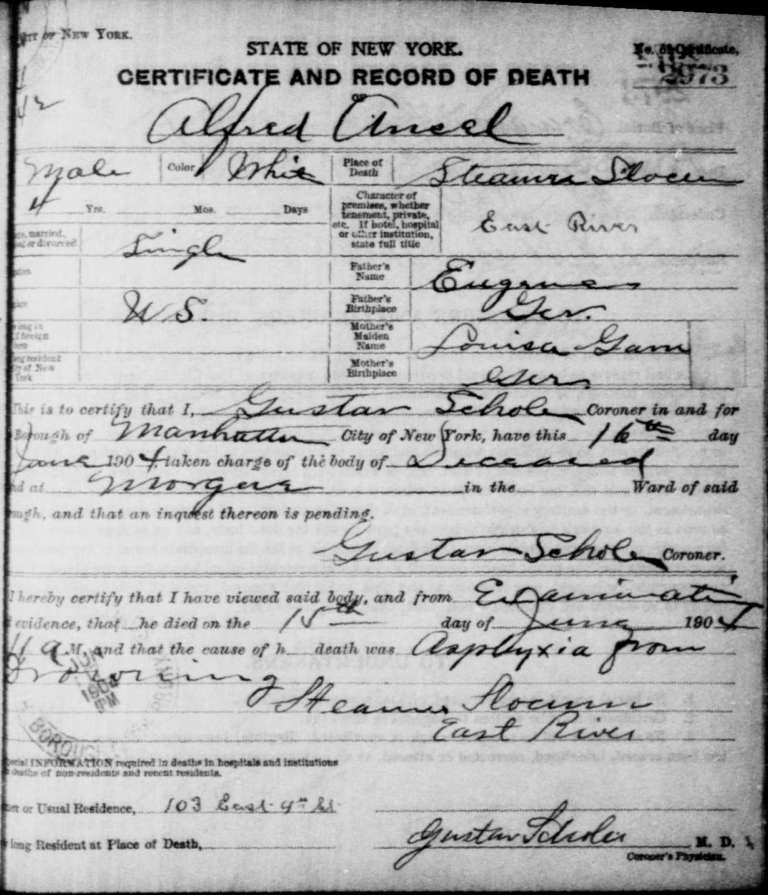

Upon hearing the news, Eugene rushed to the temporary morgue in a warehouse on the East 26th St. dock. He was so distraught, he misidentified five bodies as his wife Louise. However, the coroner found the best way for Eugene to be sure: Louise’s wedding ring had the couple’s initials. She was identified, as was son Alfred the next day; son Eugene was never found.

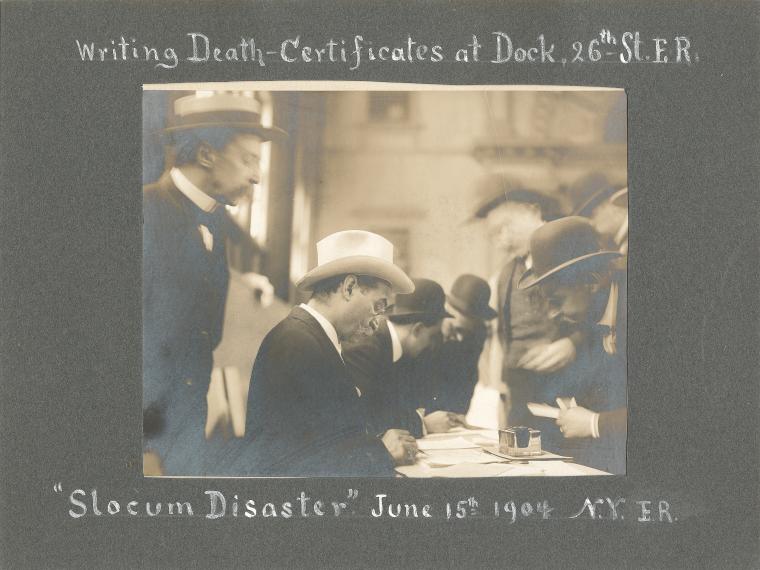

Many of the death certificates from the disaster are hurriedly scrawled and incomplete. The scene in the morgue was trying for all, but most of the anxious relatives were hoping not to find their loved ones, hoping they were in one of the hospitals treating the injured. There is a photo of Dr. Gustav Scholer, chief coroner in New York and a German immigrant, signing a death certificate in the 26th St. dock temporary morgue:

Eugene was devastated by the loss of his family. He buried his loved ones in Evergreen Cemetery, closed his deli and, like many residents of Kleindeutschland, left the mournful neighborhood and moved uptown, not far from where he and Louise had lived earlier.

A year and a month after the disaster, on July 29, 1905, Eugene married again. Leonie Stimpfling was a teenager, 16 years younger than Eugene, willing to mend his broken heart. She was also from Guebwiller! She had arrived with her widowed mother Caroline in May 1898 to join her brother. They had sailed aboard La Bourgogne, a four-masted steamship, the very ship Eugene had taken six years before. Luck was on Leonie’s side, for three months after her arrival, La Bourgogne sank in a collision in the Atlantic, with great loss of life.

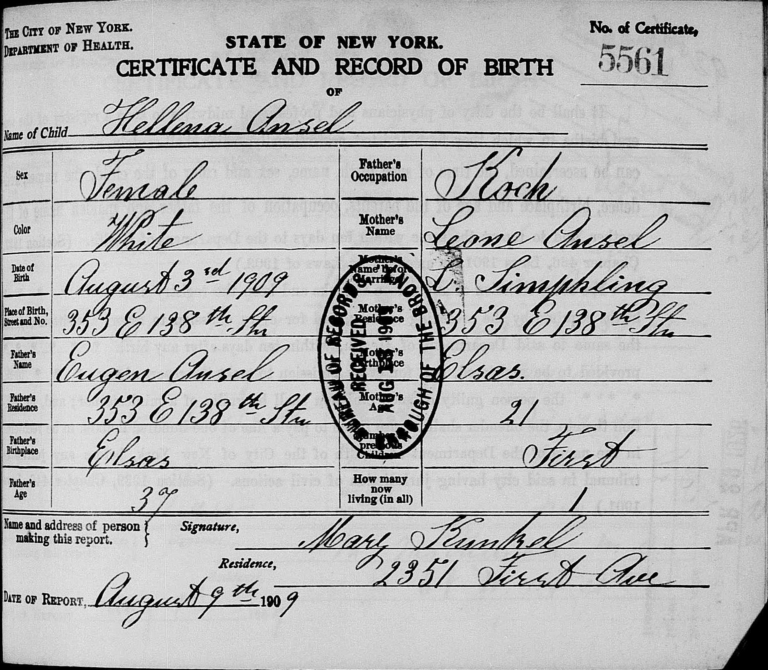

In 1909, the couple had a daughter, Helen. The midwife who reported the birth was clearly an Alsatian or German speaker. Note the words “Koch” (cook) and “Elsas” (Alsace):

Moving Forward:

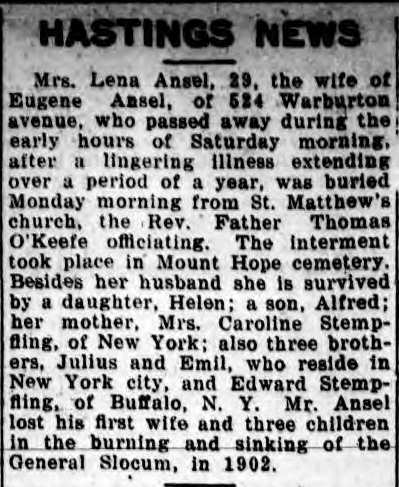

Eugene founded a deli and beer garden business in the Bronx with his good friend John Bollinger, Helen’s godfather. In 1914, Eugene and Leonie (or Lena as she was called) had a son and they named him Alfred Eugene, after the sons Eugene had lost on the Slocum. The family moved north to Yonkers, then north again to Hastings-on-Hudson where Eugene operated a deli, followed by a popular restaurant, Ansel’s Bar & Grill. Leonie died young, at age 29.

Eugene, a sociable and well-liked man, worked hard in his restaurant and by the 1930s was nicknamed the “mayor” of Hastings-on-Hudson. He often catered events and functions with hundreds of attendees and his restaurant was frequented by the worthies of Hastings. Son Alfred E. was athletic and courageous; at age 15, he risked his life to save a boy from drowning in the Hudson, a day that must have been trying for Eugene.

In the spring of 1937, Eugene had the opportunity to visit his Alsatian mountain valleys again, sailing on the liner Ile de France and no doubt visiting his brother Albert and sister Adèle. Later that year, Alfred married Helen Chomicki.

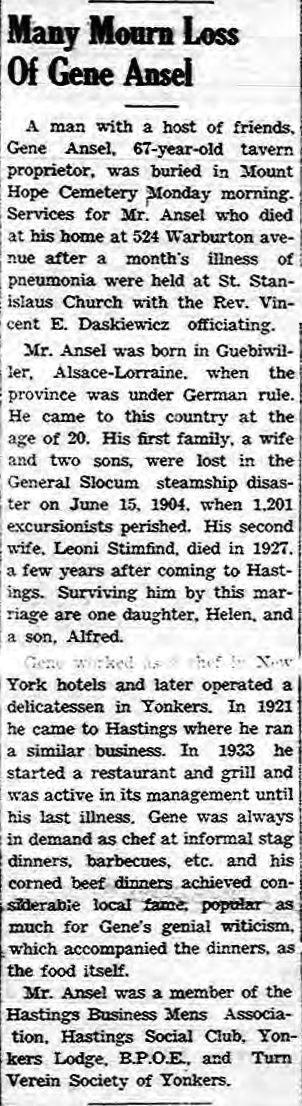

Eugene Ansel passed away on February 2, 1940, after a month long bout with pneumonia. He was widely mourned by his friends. Alfred and wife Helen operated Ansel’s for many years and had children of their own.

For More Information:

At Geneanet, we have started a collaborative family tree with every known passenger of the General Slocum, including the Ansel family. More information can be found here.

About the Author:

Sean Daly, U.S. Community Manager at Geneanet, is a French-American New Yorker fascinated by his father’s Irish immigrant family stories and his mother’s Norman ancestry. He has lived in different countries in Europe for the past thirty years and recently spent five years living in his hometown again.

Geneanet was founded in Paris in 1996 and is France’s premier genealogy site with a presence throughout Europe. Available in eight languages including German, Geneanet has 7 billion individuals indexed, 1.5 million family trees, and 4.5 million members. Geneanet has a “freemium” model, designed to help genealogists share research; a family tree of any size is free, while an affordable Premium subscription unlocks advanced search features. For more information, visit https://en.geneanet.org.

2 Responses

What an incredibly tragic day that was for Eugene Ansel and the German community of New York. I very much enjoyed reading your article Sean. Greetings from Austria!

Many thanks Nelly! The General Slocum disaster is largely forgotten today, and that’s a pity, because it was an entirely preventable tragedy which greatly impacted the German-speaking community in New York. In my youth, I lived for a time on East 3rd Street where the Slocum departed from, and walked past the former St. Marks Lutheran Church many times, but I only learned about the disaster a few years ago. The injured and bereaved family members were never compensated for their loss, not by the steamship owners who escaped justice, nor by the federal government who sent the incompetent or crooked inspectors. The survivors association worked for years with sympathetic New York politicians to obtain relief from Congress, but this never happened. However, pressure from the association did result in improved maritime safety, and the US Coast Guard which inspects vessels today often cites the Slocum disaster in their training materials.