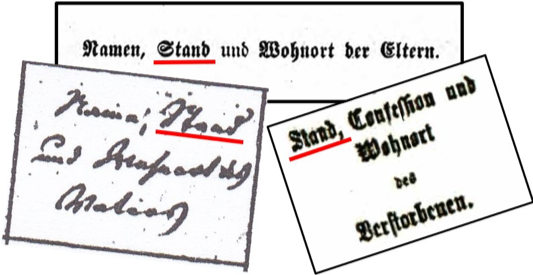

Stand is a very important word to know in German genealogy. While over time, this word has come to basically mean the profession (usually of the male named in the column), it actually is more profound than that. Some examples of the word in records is provided here:

Stand can probably best be translated as one’s standing or social status. The use of the word in both church and, to a lesser extent, civil records began centuries ago and is rooted in the history of medieval German nation. One’s station in life was preordained by God and once your ‘level’ was determined, there was virtually no upward mobility. If you began life as a peasant, you remained that for your entire life.

The structure of the system can best be described as a triangle. At the very top were God, church and Pope. Beneath that pinnacle was the emperor who was ‘selected’ by the church. One layer down came a whole host of noblemen such as princes, dukes, and marquis. Supporting these nobles were the knights and vassals and continuing down the triangle, next came the merchants and craftsman, followed by the farmers. At the very bottom of the pile were the peasants and serfs and those with “dishonorable” professions, such as an executioner, grave digger, or potter (!). Within each of the various levels were additional hierarchies of who was more important and more powerful than those below. Needless to say, you had your place in the bigger order of things and that’s where you remained. Consequently, you had your designated pew in church, as well as in your village’s parade-like celebrations.

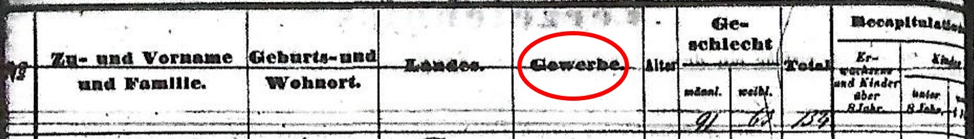

As Europe emerged from medieval times with the establishment of universities and more educational opportunities, the emphasis on your Stand or social status, became less important, but your occupation basically indicated in which tier of the triangle you resided. As a result, the many occupations given in your ancestors’ listings, is important in helping you to understand your ancestors’ life. As the industrial revolution took charge in the mid to late 1800’s, the use of the word Stand in records faded (although did not disappear!) and was replaced by Gewerbe, the German word for occupation as is seen in this passenger list of emigrants:

(By the early 20th century, the medieval class structure began to crumple, and the class of nobles was demolished with the establishment of Weimar Republic at the end of World War I.)

As you locate the records of your German ancestors in the civil registries or church books, pay attention to the entries in the columns where a Stand is requested. In some cases, the priest, pastor or scribe made no entry, but in most (not all!), it usually indicated your ancestor’s occupation, which indicated his social status. (Note that it was only very rarely that a woman’s Stand was noted, and in many of those cases, the indication was that of her husband’s or her father’s Stand, if she was unwed.)

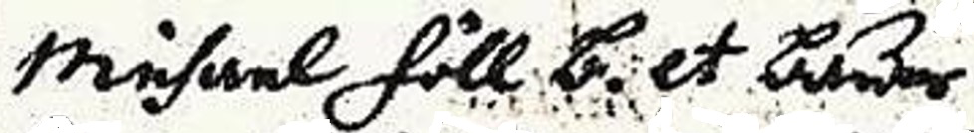

Baerbel Johnson, moderator of the Family Search German Research Wiki, provided some insight into the complexities of Stand at the first conference of the IGGP. She explained that there were basically four levels for residents of a town: Bürger (citizen), Häusler (cottager), Gärtner or Hintersassen (gardeners) and Einlieger or Hausgenossen (renters). These are the classifications for the common people who obviously were involved with some form of agriculture. These levels show the hierarchy of these farmers in the lower tier of the triangle and indicate that ownership of some land gave you more prestige and a higher Stand. (More than likely, a Bürger had voting rights within the town, whereas a Häusler and below did not.) Here is an entry where the ancestor is listed as a B et Bauer – B, the abbreviation for Bürger; et, French for und, and; and Bauer, farmer, so he obviously has some status in town, since he’s not just a farmer:

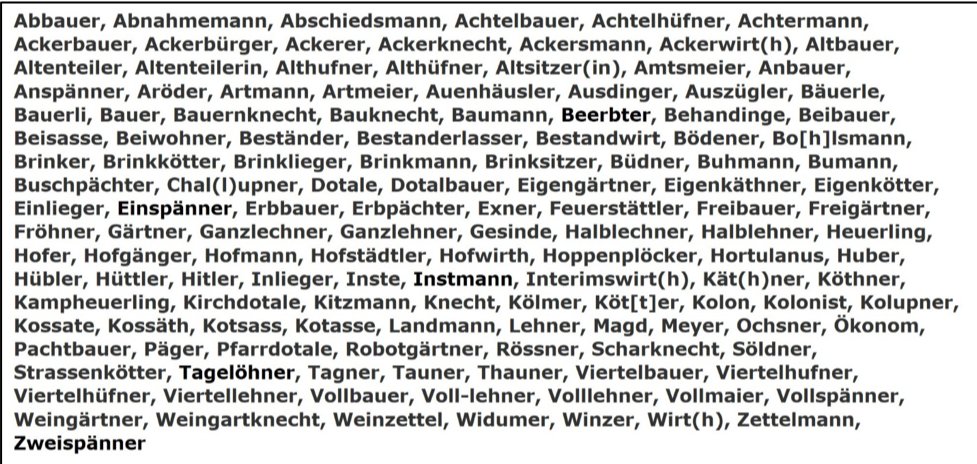

At that very same conference, Baerbel discussed the many, many German words that researchers will find in records that name a type of farmer in medieval Germany. The Family Search Wiki has in its dictionary 150 different terms for farmer, as illustrated here:

The list is extensive, but it is by no means exhaustive! It can be found at: https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/German_Genealogical_Word_List#Types_of_Farmers

While many of the names for farmers come from dialectic German and are found in that particular region of the German-speaking nations, there are other words naming farmers that are not in the list at all. For example, Ernest Thode’s German-English Genealogical Dictionary does not have an entry for Kotasse, but does include similar words such as Kossat, Kossate, Koter, which may all be dialectic versions of the same type of farmer. Needless to say, if you don’t find the word from the record you found in one place, look in another historic dictionary. (A modern German-English dictionary will not be of much use, since many of these terms have fallen from use in 21st century Germany.)

If you have discovered ancestors who were not in the agriculture profession, you will need to check Thode’s dictionary or websites that focus on German professions.

A fairly comprehensive list of occupations can be found at http://sites.rootsweb.com/~romban/misc/germanjobs.html. You will not find any listings under the letters G or H, as those two are still under construction. All umlauts have been replaced with ae, oe, or ue.

Another list of old German occupations can also be found at https://www.jewishgen.org/infofiles/GermanOccs.htm . Part of the beauty of this site is that lists of these same jobs are available for Polish, Hungarian and Romanian, all translated into English.

Another very thorough list of old German professions can be found at: http://www.european-roots.com/german_prof.htm This list is sorted by categories, not alphabetically, and is entirely in German. Use Control-F to type in the German word you are seeking in the list.

The issue of a German ancestor’s Stand/occupation is an interesting one indeed. While we may never fully understand the class structure of medieval Germany, I hope this article has provided you with a little insight into a very complex subject. And unlike me, I hope that you aren’t disappointed by what you discover about your ancestors’ professions. Sadly, a Weber, Weaver, is also considered a dishonorable profession!

As a native Pennsylvania Dutchman, Ken Weaver can trace most every line of ancestors to an 18th century German or Swiss immigrant, so it was only natural that he learn to speak German and did so in high school under the tutelage of an inspiring immigrant German teacher. Majoring in German at Millersville University, he also studied at Philipps-Universität and upon graduation began a career as a German teacher. He went on to become a principal, but continued his language studies by earning certification in ESL. Upon retirement from the public education, he taught at the university level until recently moving to Florida. Now he works on his genealogy, and as a member of several different societies, spends considerable time teaching language tips to any genealogist who’ll listen! He can be reached at kenneth.n.weaver@gmail.com .

One Response

Thanks so much, Ken Weaver for being a guest. This is a great article – so interesting and very helpful. I think I have a “Schildbauer” in one of my letters, and I don’t understand yet was für ein Bauer es ist, but will check out your links. I get very different suggestions from DeepL and Google Translate. I may have to go straight to Baerbel in the community. I met you at IGGP in Sacramento. With luck, there will be another such fine conference one day.

Josephine Lindell