When tracing Eastern European ancestors, it is no secret that church registers and civil registration of births, marriages, and deaths are the most popular and useful sources for extracting important genealogical information. However, there are other record groups to be searched that may prove useful for gleaning additional details, especially in the absence of church and vital records for your locality. This article will discuss five other key resources you might be missing.

Before You Search

Remember there are two key pieces of information you need to have before you can successfully trace your ancestors in the old country:

- You must learn the immigrant’s original name.

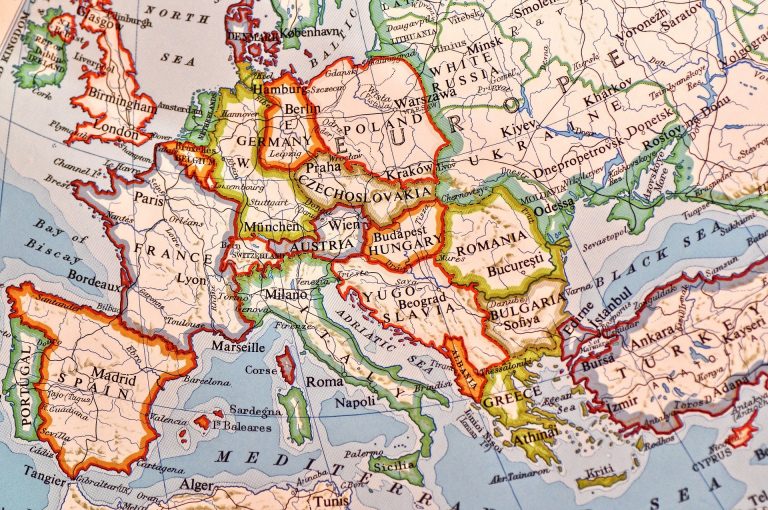

- You will need to obtain the specific name of the town or village of origin from searching records created for or about the immigrant after arrival, and then using maps, atlases, and gazetteers to pinpoint current and historical locations.

Search Strategy

Many one-of-a-kind resources (letters, photographs, and other ephemera) exist in libraries (especially those with dedicated Slavic/Eastern European collections), historical societies, ethnic genealogical societies, and museums located throughout North America. You will also want to extend your search to similar repositories in Europe. Accessibility and availability will vary by country and local area. Privacy laws may apply.

Below is an overview of some of the most overlooked resources.

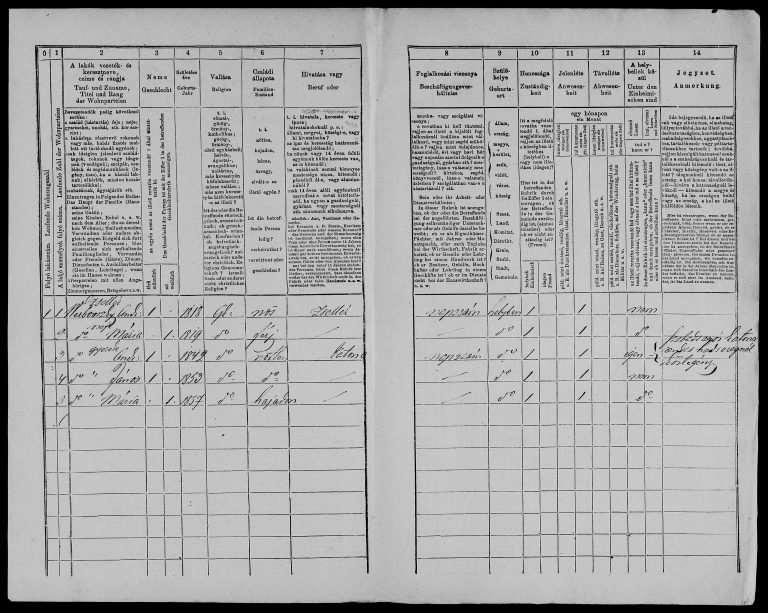

1. Census Records.

As you probably learned from exploring US or Canadian census records for your ancestors, the prime value of census records is for grouping families together. In Eastern Europe, censuses were usually taken for tax and military conscription purposes. Searching census records can be hit or miss depending on the country, the region, and whether or not registers have been preserved. Because of shifting borders and the destruction of records during wartime hostilities, only relatively small portions of certain record groups survived in many instances. Therefore, you should check registers of births, marriages, and deaths (not census records) first, opposite of what genealogists typically do when looking at North American records for their ancestors. However, locating a family in a census record can help you place them in a particular location at a specific time period. Check the FamilySearch Wiki by country and look for a Census Records tab.

2. Military Records.

Military records are often considered a secondary resource because they are not easy records to locate. To find military records for the various armies in the Austrian, German or Russian empires, you will first need to understand the history of the time period in which your ancestors lived, as this determines whether your ancestor served during the Partitions of Poland, the Austro-Hungarian rule over the Czech and Slovak republics, etc. Next, you will need to know how the process of conscription worked and the regiment/military unit your ancestor served in. Finally, you will need to become familiar with the types of records (e.g., muster sheets, personnel sheets, military citations), which vary by regiment and period. Two excellent sources for research advice include, A Guide for Locating Military Records for the Various Regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Carl Kotlarchik , and several excellent articles available from The Foundation for East European Family History Studies including the “Russian Central State Military Historical Archive” and “An Introduction to Austrian Military Records” by Steven W. Blodgett.

3. Land Books, Cadastral Surveys, and Tax Lists.

Land records, cadastral surveys, and tax lists are other documents that can provide additional clues about your ancestors. While often difficult to track down, land records may serve to fill in some of the generational blanks in a family tree, and tax lists can offer a glimpse into an ancestor’s financial and social status. Land records are primarily used to learn where an individual lived and when he or she lived there. They often reveal family information such as a spouse’s name, heir, other relatives, or neighbors. You may learn where a person lived before, occupations, and other clues for further research. The primary advantage of using land records is that they go back further in time than the parish registers of births, marriages, and deaths. Often, the same land was passed from generation to generation. Land records may be deposited in various archives, so you should check with the archivist to make sure you’re searching in the correct places. Cadastral maps were created to determine the economic potential of manors. Maps of manors depicted the actual configuration of farms, with bodies of water, roads, and other natural objects. The maps are accompanied by description books, which describe garden plots, fields, hay lands and pastures, and more. Just as we do, our ancestors paid taxes, and documentation from this process can be another potential source. In some countries, you will find revision lists that contain personal data on household members. Consult the FamilySearch Catalog, or check with state, regional or local archives.

4. Emigration Documents/Passports.

Most genealogists look for incoming passenger lists, but in some instances, there may be documents such as emigration lists, permissions to emigrate and records of passports issued. The information in these records may include the name, age, occupation, destination, and place of origin or birthplace of the emigrant, but if you don’t find them among family documents, they can be difficult to locate and typically reside in state or regional archives. Some countries kept records of those who left. Ancestry.com has Hamburg Passenger Lists, Handwritten Indexes, 1855-1934 and S., Passport Applications, 1795-1925 searchable online. To view a variety of passport documents, check out the Flickr Passport Photos collection by user mákvirág.

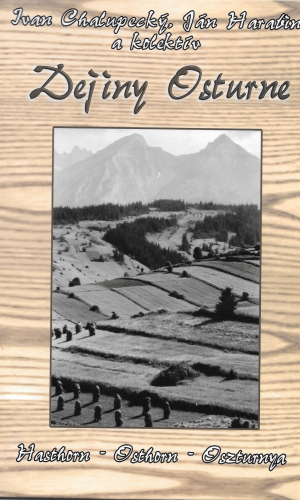

5. Town or Village Histories.

Individual towns or villages may also have published histories. These sources can come in book form or published or town or village websites. Search for the town or village name on Google, as your ancestors’ names could be mentioned in these narratives. While it could be a challenge to obtain a copy if you don’t have any living relatives in the town or village, you can always try contacting the local historian or mayor or check if the village has a page on Facebook. For example, my maternal grandfather’s family is mentioned in a book (Dejiny Osturne) about Osturňa, Slovakia, that was published by historians there. I also recently learned of a book about one of my other ancestral villages, Kučín, which mentions my book Three Slovak Women, and my 2010 visit there!

Keep in mind that records are organized by location so be sure to check all parishes, archives, and local register and mayor’s offices in the ancestral town or village. While some record sets may be available online, others exist on microfilm or in print form, through FamilySearch or country-specific archival and other websites, so be sure to check back periodically for new or updated collections.

Lisa A. Alzo, M.F.A., is a freelance writer, instructor, and internationally recognized lecturer, specializing in Eastern European research and writing your family history She is the author of 11 books and hundreds of magazine articles. Lisa works as an online educator and writing coach through her website Research, Write, Connect, https://www.researchwriteconnect.com and developed the Eastern European Research Certificate Program for the National Institute for Genealogical Studies. Visit https://www.lisaalzo.com for more information.

One Response

Do they have census records in Germany? How do you get a copy of passports – my Great Grandfather came over with his wife and two children? I have the immigration record but would like a copy of the passport?