Deciphering names in genealogical documents can be a bit of a challenge. After all, you can’t just look in the dictionary to see if your transcribed name is correct. Having a grasp on the German naming system, therefore, can be very helpful for your research. Remember these ten facts below, and understanding those German names will become much more simple!

- “in” on the end of a last name is usually just a grammatical marker, indicating that the person with that last name was a female. My last name, Schober, may have been written “Schoberin” on a church record or certificate. When I am translating from German to English, therefore, I simply leave off the “in” of the last name, as it is a mere suffix to show that I am a female.

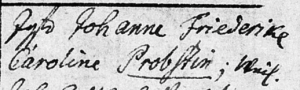

This record reads “Jgfr (Jungfrau – Miss) Johanne Friederike Caroline Probstin”. Her last name would actually be Probst.

This record reads “Jgfr (Jungfrau – Miss) Johanne Friederike Caroline Probstin”. Her last name would actually be Probst.

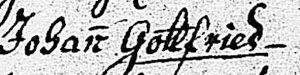

2. A straight line over a letter in a name will usually mean that the letter below is an “n” or an “m”, and that it should be doubled. You may see this on names such as “Anna” and “Johann”, and in last names as well.  The “n” in Johann has a line above it. This means it should be doubled, and written as “Johann”.

The “n” in Johann has a line above it. This means it should be doubled, and written as “Johann”.

3. Names were sometimes written in the “normal” Latin script (the script we use) instead of the old German handwriting. You may have a document that’s written entirely in the old German script, but with your ancestor’s name written in a script that looks like our modern cursive.

Here the name August is written in the normal Latin script – no “swoops” above the “u”, a regular cursive “s”, etc.

Here the name August is written in the normal Latin script – no “swoops” above the “u”, a regular cursive “s”, etc.

4. If you see a name underlined in your document, that means that this name was the Rufname, or the name your ancestor was called. Below, the child listed is “Johann Gottfried”. As “Gottfried” is underlined, this would have been the name his family called him.

5. In older documents, you may see the Latin suffix “us” on a male name: Jakobus, for example, instead of Jakob. This is the same name, so it is important to recognize both variations in your records.

6. If an older sibling died in childhood, their name may have been used for the next child born (assuming it was also a boy or a girl).

7. Children were often (but not always) named after their godparent or baptismal sponsor. If you can’t read the name in the child’s column, look to the godparent/sponsor column to: 1)See if it could be the same name, and 2) To see if that name is easier to read there.

8. “chen”, “lein”, “l”, “el”, “erl” are diminutive suffixes in German (the final three are more common in Bavaria and Austria). A young Barbara, for example, may have been called “Barbchen”. This would be the English equivalent of writing “Danny” for “Daniel.”

9. Spelling was not always the same from record to record. You may see the name Jakob in one record, Jacob in the next, and Jakobus in the third. Knowing the different variations of names and spelling can be very helpful, as it allows you to broaden your search for your ancestor. See Think Like A German: Spelling Variations in German Documents for more information.

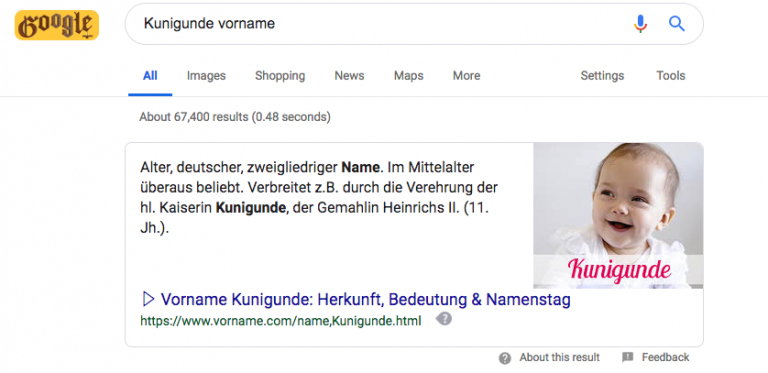

10. If you aren’t sure if a first or last name exists, google “name guess + vorname” or “name guess + nachname) and see if any results come up. “Vorname” means “first name”, and “Nachname” means “last name”. This will show you if your transcription guess exists in German.

Above, I typed in “Kunigunde + Vorname” to see if Kunigunde is a name in German. Looks like it is!

Now that you know some tips about the German naming system, it’s time to go out there and find the names of your ancestors. Enjoy filling in that family tree!